The following is a guest post by Bryan Dowd, Mayo Professor of Health Policy and Management at the School of Public Health, University of Minnesota.

The oral arguments in King v Burwell at the Supreme Court have prompted a discussion of “death spirals” in the health insurance market. The prospect was raised alternately as one, potentially coercive outcome for states failing to establish their own exchanges and as one Congress could not have intended.

Larry Levitt of the Kaiser Family Foundation states unequivocally that if premium subsidies are withdrawn from residents of states with federally-run exchanges:

The result in affected states would be a classic “death spiral.” Premiums would rise, more healthy people would drop their coverage, and that in turn would cause premiums to rise even more. This would destabilize the whole individual market in these states because insurers are required to set premiums within a state based on their entire individual market business, not just people buying through the marketplace.

But would withholding premium subsidies from residents of states with federally-run exchanges necessarily result in “death” of the insurance market?

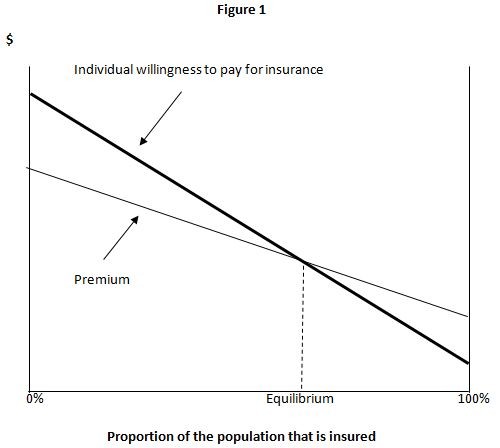

Figure 1, adapted from two prior papers I wrote with Roger Feldman, illustrates the problem. The horizontal axis in Figure 1 shows the proportion of the population that is uninsured. The vertical axis measures dollars per person. The two sloping lines represent the actuarially fair premium for health plans in the market and the individual’s willingness to pay to be insured. Willingness to pay represents the individual’s level of risk aversion. (The lines do not have to be either lines or strictly linear. They could be replaced with downward sloping scattergrams and varieties of curvature.)

An important feature of the diagram is that individuals join the insured sector roughly in order of their health risk. That feature is required in order for there to be any coherent story about death spirals. The left-hand side of the horizontal axis represents only the least healthy person enrolled in insurance. The premium is relatively high, but so is the individual’s willingness to pay for insurance. The important point is that the individual’s willingness to pay exceeds the premium, and thus the individual chooses to be insured.

Movement along the horizontal axis from left to right represents progressively healthier individuals choosing to become insured. Their willingness to pay for insurance declines, but their decision to join the insured sector drives down the average (community-rated) premium. Enrollment of ever-healthier individuals continues until the average premium exceeds the healthier individual’s willingness to pay for insurance. The equilibrium occurs because willingness to pay declines faster than premiums.

The basic diagram allows illustration of two other possible outcomes (see Einav and Finkelstein).

- If the willingness to pay line lay entirely above the premium line, then 100 percent of the population would be insured.

- If the willingness to pay line lay entirely below the premium line, then no individuals would be insured. (This is the death spiral case, but there’s no guarantee this is the case we face, let alone in all markets.)

The diagram also shows that, in this case, there is no death “spiral.” Reaching the equilibrium might take time, but ultimately, the percent of the population that is insured will be determined by the location of the willingness to pay and premium lines.

There are several factors that affect the location of the lines.

- The premium line is the individual’s actual out-of-pocket premium, and thus is affected by the amount of premium subsidies available to individuals. Thus, failure to provide subsidies to individuals in states with federally-run exchanges would raise the premium line and reduce the percent of the population that is insured. But in order for there to be a “death spiral,” the withholding of subsidies would have to raise the premium line above the entire willingness to pay line.

- Premiums subsidies are based on income, and thus would go primarily to younger individuals, who tend to be healthier. The effect of removing the subsidies would be to raise the premium line, and more so on the right-hand side of the premium line.

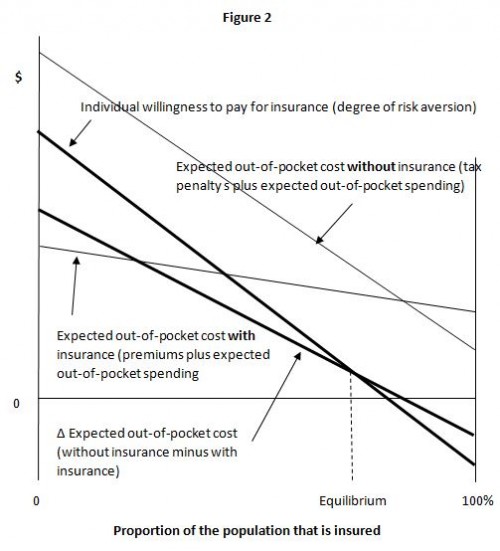

- Under the ACA legislation, choosing to remain uninsured carries its own “premium,” including the tax penalty and the risk of having to pay medical expenses completely out-of-pocket, going on Medicaid, or declaring bankruptcy, all of which could affect access to care. Figure 2 incorporates that modification.

As shown in Figure 2, individuals compare their expected out-of-pocket cost with and without insurance, and that difference, “Δ Expected out-of-pocket cost” (without insurance minus with insurance), is weighed against their willingness to pay for insurance.

The tax penalty is not related directly to health status or age, but is related to income, and thus is correlated with age. For high risk individuals, the “premium” for uninsurance is quite high, due primarily to possibility of high out-of-pocket medical expenditures, so the tax penalty probably has little effect on the high risk individual’s insurance decision on the margin.

Similarly, younger, low income, low risk individuals, may be exempt from the penalty. Their insurance decision also is likely to be based primarily on their expected health care spending, which will be low, likely lower than the premium, and thus their difference in expected out-of-pocket spending without insurance could be lower than their expected out-of-pocket spending with insurance, as shown in Figure 2.

Neither policy analysts nor the Supreme Court Justices should simply assume that withdrawal of premium subsidies from residents of states with federally-run exchanges would result in a complete “death spiral” of the health insurance market. Discussion of “death spirals” should be based on a careful analysis of the shape and location of the lines in Figure 2. They are unlikely to be linear (as drawn) and will be affected by the wide range of incentives and regulations embedded in the ACA legislation.

The Supreme Court’s deliberations present an opportunity to revisit the purpose and structure of the ACA premium subsidies. What level of subsidies would be required solely to address the possibility of death spirals versus additional concerns regarding fairness, particularly those arising from the requirement for individuals to obtain insurance or face a financial penalty?