The following is a guest post by Jennifer Gilbert, a research assistant for Dr. Ashish Jha at the Harvard School of Public Health and for The Incidental Economist. She graduated from Boston University in 2014. You can follow her on Twitter: @jenmgilbert.

Sexual violence against women on college campuses is a pervasive problem. A recent study shows that a relatively simple program can dramatically reduce it.

Researchers estimate between 20-25% of women will be sexually assaulted during four years in college, and are at particularly high risk during their first two years. While the Violence Against Women Act has pushed forward campus programs to limit sexual assault, the few that have been evaluated have shown rather disappointing results. Two workshops (here and here) showed short-term benefit, although all university sexual assault workshops but one were only conducted at a single site.

This makes the recent success of a randomized control trial on sexual assault an extremely exciting development. Senn et al. assessed whether a sexual assault resistance program could reduce the one-year incidence of rape among first year students at the Universities of Windsor, Guelph, and Calgary. You can read the protocol here.

In the intervention, female students attended a total of four scheduled intervention sessions. They were recruited via email, phone, posters, and presentations on campus. When the study began, participants took a survey, underwent randomization, and immediately attended the first of four experimental or control session The students in this study either did all of their units in one weekend or one unit per week for four weeks.

The first intervention unit provided skills to improve women’s assessment of the risk of sexual assault by acquaintances; the second taught them to recognize danger more quickly in situations that may turn coercive; in the third, participants learned self-defense; and the final unit explored attitudes, values, and desires to develop strategic sexual communication for consent and non-consent (such as role-plays on negotiating condom use).

Control sessions were more like a student health services waiting area: brochures on sexual assault were displayed and students were invited to take and read them. A research assistant also offered to answer questions in a fifteen minute group session or privately afterward at each control session. This is more than would be typical at many schools, where sexual assault is a taboo topic. The loss to follow-up was quite low, 5% or less for both the control and intervention groups, though participants were offered incentives for continued participation in both groups (extra credit for Psychology class and small gift cards).

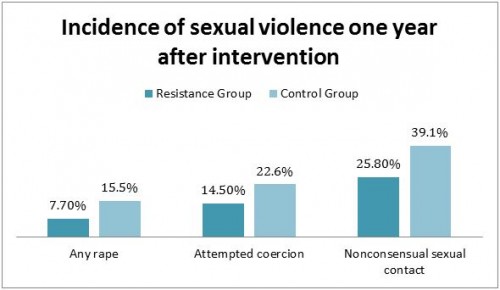

The results are impressive. One year after the units, women in the resistance program were less likely to report attempted or completed rape (p<.001), attempted coercion (p=.001), and nonconsensual sexual contact (p=.001) over the course of the year (see figure). Most previous programs require “booster sessions” every one to two months to maintain an effect, but this program didn’t use any booster sessions after the main intervention and still had tremendous results after a full year.

So what made this program so effective? The major differences between this intervention and others were that this one had greater hours of programming time, more interactive and practice exercises, a stronger focus on escalation of resistance in response to unwanted sexual advances, and positive sexuality content that supported participants in expressing their sexuality in a variety of ways and pursuing relationships that they were comfortable with, rather than shaming participants for their sexual preferences.

Of course, there are limitations. Participants were not blind to their intervention vs. control status. The outcomes were self-reported. These two limitations lead to the possibility that some of the differences between study arms were due to differential reporting, as opposed to differences in experiences. However, it’s not clear if women who underwent the intervention would be more sensitized to report assault or less likely to because they would be ashamed they could not successfully deter it after going through the program. Most importantly, this program is not a catchall. It does not address male students who perpetrate or experience sexual violence, an extremely under-studied area that merits attention. The program also gave continuous incentives that average universities might not be able to provide.

Despite these limitations, the study suggests that more can be done on campuses to protect women from sexual assault. It’s hard to argue that the status quo standard of prevention and care is adequate.