There is a lot of over-treatment in US medicine: the use of medications and procedures that deliver little or no benefit, increase the cost of care, and expose patients to unnecessary harm from side effects. How can we change this? It’s a deeper and harder problem than it looks.

There is a lot of over-treatment in US medicine: the use of medications and procedures that deliver little or no benefit, increase the cost of care, and expose patients to unnecessary harm from side effects. How can we change this? It’s a deeper and harder problem than it looks.

A case in point is the use of proton pump inhibitor medications (PPIs, familiar brand names include Prilosec and Prevacid) for the treatment of supposed gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in infants. GERD is a severe problem in which the esophagus is eroded by regurgitated stomach acid. PPIs have been shown to be an effective treatment for this condition.

However, the GERD diagnosis has increasingly been applied to infants who do not have the specific physiological symptoms of GERD, but who spit up and cry frequently and are hard to soothe. These latter infants are now frequently treated with PPIs. As Eric Hassall explains in the Journal of Pediatrics,

in the 6 years from 1999 to 2004, there was a >7-fold increase in PPI prescription. One of the PPIs… saw a 16-fold increase in use during that 6-year period…

Writing with a sarcasm unusual in a scientific journal, Hassall notes that

These data would imply that somehow the diagnosis of GERD has been missed over the past several decades or has recently become a major scourge of infants in the developed world, with acid suppressing drugs becoming a new essential food group in their own right. This change in practice has come about for several reasons, none based in medical science.

It has been true forever that lots of babies spit up a lot, cry a lot, and are difficult to soothe. And the great majority of these babies have been successfully ‘treated’ with long walks, car rides, rocking chairs, but mostly just waiting while the babies grow out of it. This is exhausting and stressful for parents. Hassall believes that the growth in the use of PPIs occurred because extensive direct-to-consumer advertising for PPIs and similar medications for adults popularized the term “acid reflux.” So it made sense to parents that these drugs would provide a solution for a seemingly intractable problem. And for doctors, calling the problem GERD and prescribing a PPI to the infant was a way to at least soothe the parents.

The problem with that is that randomized controlled trials provide no evidence that PPIs are better than placebos for difficult infants without objective evidence of GERD. So we have a classic quality problem. PPIs are relatively but not completely safe, they cost money, and they provide no benefit when prescribed beyond a severely ill population.

How do we fix this? One straightforward idea is that we should inform parents about the lack of efficacy of these drugs. If only it were that simple. Laura Scherer and her colleagues ran an experiment to understand how getting a diagnosis for your child affects how parents understand what doctors tell them about the benefits of PPIs.

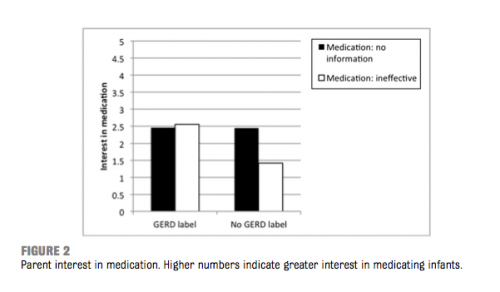

Parents read vignettes in which doctors talked about PPI treatment for a baby with non-specific GERD-like symptoms. There were four kinds of vignettes. Half the parents were told that the baby had GERD and half were not given a diagnosis. And half the parents were told that PPIs were ineffective, while half were told nothing about PPI effectiveness. All other information about the baby’s symptoms and the safety of the medication was the same.

The Figure shows that when the doctor did not tell the parents that the baby has GERD (the two right hand bars), telling the parents that PPIs were ineffective reduced the parents’ interest in the medication, just as one would expect. But when the doctor told the parents that the baby had GERD, being told that PPIs were ineffective had no effect on their interest in medicating their children.

Why did this happen? Interestingly, it’s not the case that the diagnosis made parents believe that the babies were more ill.

The GERD label had no impact on parents’ perceptions of illness severity, both in terms of reported amount of worry, and perceived seriousness.

Getting a diagnosis, I speculate, activated a mental schema that “my baby has reflux disease, therefore she needs an acid-reducing medicine”, and this neutralized the information that “PPIs don’t work.”

So simply getting a diagnosis can have a harmful side effect on parents’ understanding of physician communication. This is a quality problem in doctor-patient communication: we need to find more effective ways to explain drug efficacy to patients.

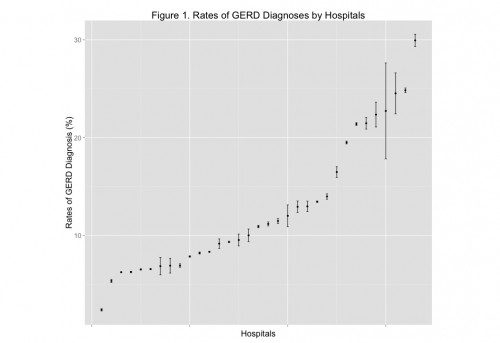

But the quality problem is even deeper than that. Here are some data that I have gathered about the rates of GERD diagnosis in neonatal intensive care units across US pediatric hospitals.

The hospital on the far right diagnosed GERD almost 13 times more often than the hospital on the far left. It is very difficult to believe that this is just a matter of varying rates of GERD across hospitals. It is likely that there is substantial lack of standardization in how the diagnosis is given. So there is another quality problem: many babies are getting diagnosed with GERD when they do not really have it, which helps generate unnecessary PPI prescriptions.

The bottom line is that the US healthcare cost problem is in part a quality problem. Quality of healthcare is like an iceberg. On the surface, there are frightening stories about amputations of the wrong limbs and fatal medication errors. But 90% of the problem is below the surface, in routine but surprisingly difficult tasks like diagnosis and doctor-patient communication.