This is the first of an occasional series of posts that summarize my academic journal articles. This post has been cited in the 20 August 2009 Health Wonk Review, hosted by Health Business Blog.

My most recent publication is the 2009 Health Care Financing Review article Payment Reduction and Medicare Private Fee-for-Service Plans by Frakt, Pizer, and Feldman. Below is the abstract followed by an explanation of the contributions the work.

Medicare private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans are paid like other Medicare Advantage (MA) plans but are exempt from many MA requirements. Recently, Congress set average payments well above the costs of traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare, inducing dramatic increases in PFFS plan enrollment. This has significant implications for Medicare’s budget, provoking calls for policy change. We predict the effect of proposals to cut PFFS payments on PFFS plan participation and enrollment. We find that small reductions in payment rates would reduce PFFS participation and enrollment; if Congress reduces payments to traditional FFS levels it would cause the vast majority (85 percent) of PFFS plans to exit the market.

As is clear from the abstract the paper is about PFFS plans, which are a particular type of MA plan. In brief, MA plans are private Medicare plans (mostly HMOs) that receive payment from the government to provide benefits to Medicare beneficiaries. PFFS plans are a type of MA plan but they are not like HMOs: they do not have to set up provider networks and they pay providers on a fee-for-service basis using the traditional Medicare fee schedule.

PFFS plans are the closest thing to direct privatization of traditional Medicare. To a good approximation you can think of them as private organizations that get paid to do what the government already does. For more background reading on MA and PFFS plans see my prior post Medicare’s Structure and Payment Systems, Part II: Medicare Advantage.

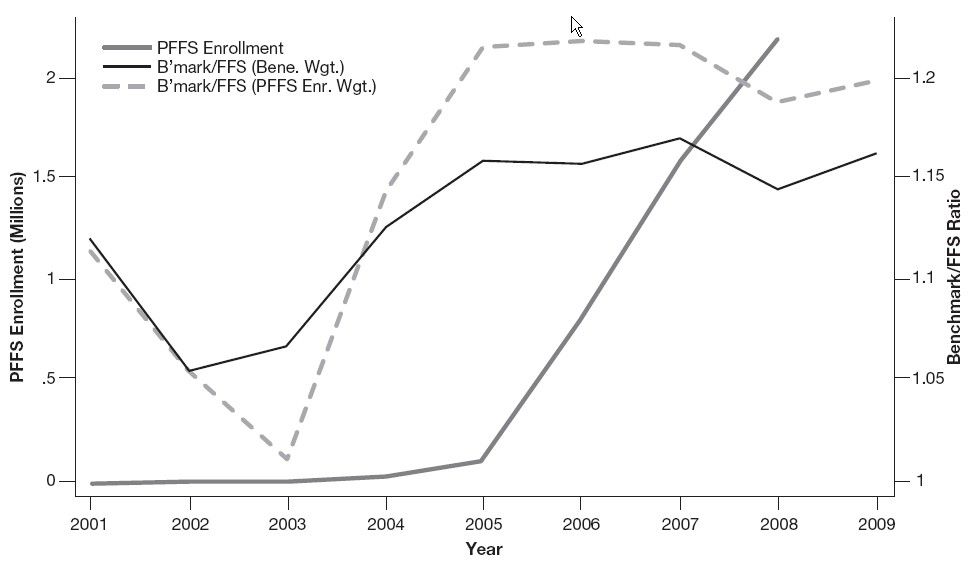

The article makes two main contributions. The first is a 2001-2009 time series of Medicare payments to MA and PFFS plans relative to the average cost of a beneficiary enrolled in traditional FFS Medicare. To the authors’ knowledge such a time series had not yet been provided elsewhere (it is a non-trivial exercise to compute this time series in a consistent manner).

The time series is shown below (click to enlarge). It reveals that, relative to FFS costs, payments to MA (thin solid line) and PFFS plans (dashed line) have been above one in all years and particularly high since 2004. Subsequent to the increase in payments since beginning in 2004, enrollment in PFFS plans increased dramatically (thick solid line). (There is a technical detail pertaining to a change in payment methodology beginning in 2006. That’s why the term “benchmark” (or “B’mark”) is used in the figure. Roughly speaking you can interpret this as the payment to plans. More accurately it is the maximum possible payment.)

To make it explicit, that MA or PFFS payment relative to FFS costs is above one means that it costs Medicare (and taxpayers) more to cover the care of a beneficiary enrolled in an MA plan than in traditional FFS. The extra payment to MA plans is supposed to be used to provide coverage more generous than that available under FFS Medicare and at least some of it does since MA benefits are richer and cost sharing lower than FFS Medicare.

But why are are taxpayers paying private plans more to do a job that has traditionally been done by the federal government for lower cost? Of course the answer is “politics.” There has been an effort to expand the role of private plans in Medicare, in particular attracting them to rural areas with payment rates higher in proportion to FFS costs relative to non-rural areas. In rural areas provider networks are costly or impossible to set up due to the lower density of providers. Since PFFS plans are not required to establish provider networks they have disproportionately thrived in rural areas (relative to other MA plans). Hence, PFFS plans are the costliest plan type, relative to FFS. This is widely known and the article makes the point again with a 2001-2009 time series.

The second main contribution of the paper is to illustrate with a simulation what might happen if payments to private plans are cut, as has been proposed by MedPAC, CBO, and others. After estimating a model of PFFS participation in Medicare using public data, my co-authors and I simulated the effect of implementing payment parity (payments at 100% of FFS cost). We find that such a policy would nearly wipe out PFFS plans, reducing their participation by 85%.

This degree of payment reduction appears to be the direction the Administration and Congress want to go. Of course they won’t just cut payments to PFFS plans but to all of MA. Many beneficiaries will lose the generous coverage they currently enjoy under the program, but taxpayer dollars will be saved (or, rather, redirected into health reform).