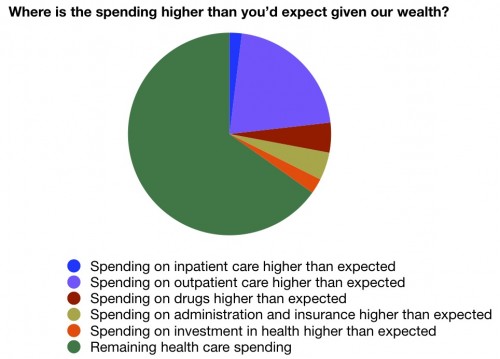

If you haven’t read the introduction, go back and read it now. That introductory post also includes links to all the posts in this series on what makes our health care system so expensive. Each of these pieces is going to discuss one of the components of unexpected spending that accounts for why our system is so expensive.

Remember, these posts are going to follow a common theme. I am going to highlight how the United States is spending more than you’d expect given our wealth. Much of this comes from the McKinsey & Company study, Accounting for the cost of health care in the United States.

Investment in health is made of three categories: (1) prevention and public health, (2) public investment in research and development, and (3) investment in medical facilities. It may surprise you (it certainly did me), that the United States spends a surprising amount in this category – $144 billion in 2006. Still more surprising is that this is more than you would expect given out wealth, $50 billion more than you would expect.

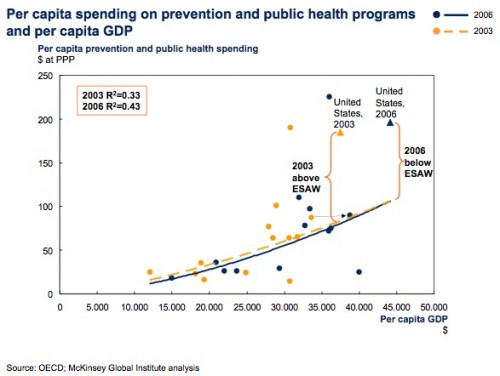

In the first category, prevention and public health, the US spent $59 billion in 2006, $27 billion more than you’d expect given its wealth. Most of that was spent by states ($49 billion) for community health centers, tobacco prevention, and public health departments. The remaining $10 billion, spent by the federal government, mostly goes to the CDC and FDA.

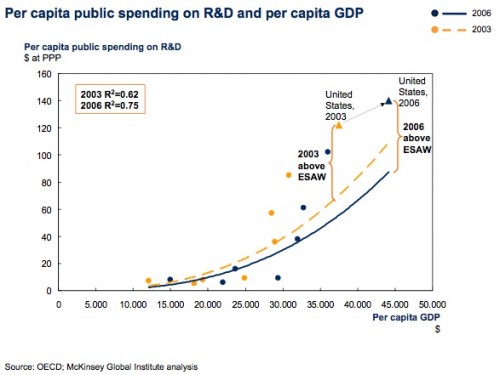

In 2006, the US spent $42 billion in public funds on research and development. Most of that ($28 billion) went to the NIH. This does not include private investment by corporations, like pharma.

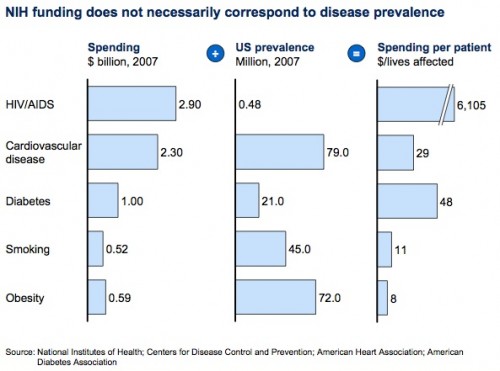

While the total amount we spend on research is actually $16 billion more than you’d expect given out wealth, and it’s hard for me to argue that more money for research is a bad thing, there are reasons to suspect the extra money isn’t being spent wisely. The McKinsey report notes that spending often does not align with disease prevalence:

There’s nothing that says that spending has to align with disease prevalence. There are reasons it might not. Perhaps we might want to align spending in terms of cost-effectiveness. Perhaps we want to align spending to knock off easy targets first. Unfortunately, it doesn’t appear that we choose our research spending in an easily understood fashion.

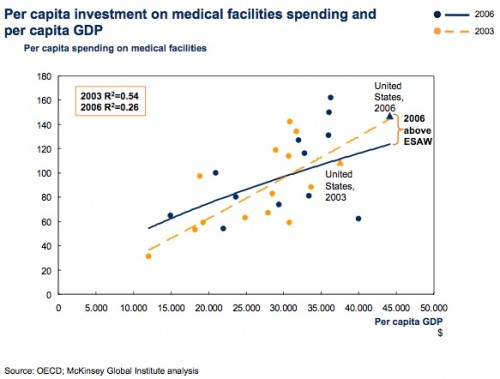

The final source of investment in 2006, that in medical facilities, was $44 billion, or $7 billion more than you’d expect given wealth in the US. Most of that money ($36 billion) was spent by private industry, and more than two-thirds of that was to build new hospitals or extend older ones.

Investment spending is not straightforward. Yes, we spend more on average than other countries. But we’re not necessarily spending it wisely. Our investment money isn’t directed where it might do the most good. Our national investment in public health is shockingly low. And is increasing our hospital capacity and number really a good idea given the fact that it’s likely increasing our spending on inpatient care? The knee jerk reaction will be to cut this spending on public health or investment in research as we might in other categories, but that may do more harm than good.

By now, you couldn’t really still be expecting easy answers, were you?

I will say this at the end of every one of these pieces. None of this proves that this money is wasted or fraudently taken. Nor am I saying that we shouldn’t spend more money than other countries. But this is money that goes above what you’d expect us to spend based on our greater wealth. We should at least be able to account for and explain this increased spending in some way.