The following originally appeared on The Upshot (copyright 2019, The New York Times Company). It is jointly authored by Austin Frakt and Toni Monkovic.

When the opioid crisis began to escalate some 20 years ago, many African-Americans had a layer of protection against it.

But that protection didn’t come from the effectiveness of the American medical system. Instead, researchers believe, it came from racial stereotypes embedded within that system.

As unlikely as it may seem, these negative stereotypes appear to have shielded many African-Americans from fatal prescription opioid overdoses. This is not a new finding. But for the first time an analysis has put a number behind it, projecting that around 14,000 black Americans would have died had their mortality rates related to prescription opioids been equivalent to that of white Americans.

Starting in the 1990s, new prescription opioids were marketed more aggressively in white rural areas, where pain drug prescriptions were already high. African-Americans received fewer opioid prescriptions, some researchers think, because doctors believed, contrary to fact, that black people 1) were more likely to become addicted to the drugs 2) would be more likely to sell the drugs and 3) had a higher pain threshold than white people because they were biologically different.

This accidental benefit for African-Americans is far outweighed by the long history of harm they have endured from inferior health care, including infamous episodes like the Tuskegee study. And it doesn’t remedy the way damaging stereotypes continue to influence aspects of medical practice today. “The reason to study this further is twofold,” Dr. Kolodny said. “It’s easy to imagine the harm that could come to blacks in the future, and we need to know what went wrong with whites, and how they were left exposed” to overprescribing.

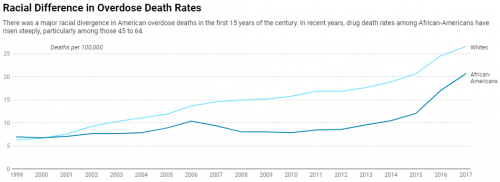

The prescription-opioid-related mortality rates of black and white Americans were relatively similar two decades ago, but researchers found that by 2010, the rate was two times higher for whites than for African-Americans.

Because African-Americans were less likely to receive those prescriptions, they were less likely to become addicted (though they were more likely to endure unnecessary and excruciating pain for illnesses like cancer).

The researchers, Monica Alexander, a statistician with the University of Toronto; Mathew Kiang, an epidemiologist at Stanford; and Magali Barbieri, a demographer at the University of California, Berkeley; published their study in the journal Epidemiology.

With additional analysis at The Upshot’s request, Mr. Kiang calculated that had the African-American population’s mortality rates caused by prescription opioids been equivalent to those of whites, black Americans would have experienced 14,124 additional deaths from 1999 to 2017.

It’s a counterfactual analysis that relies on some large assumptions. Among other things, the projection assumes that the public health and medical response to the epidemic would have remained the same even if the African-American mortality rate had been higher. And it doesn’t take into consideration any potential changes in overdoses from heroin and fentanyl had African-Americans had greater access to prescription opioids. Still, Mr. Kiang found the results “fairly remarkable in at least two ways.”

“First, it’s a good example of how more medical care is not necessarily a good thing,” he said. “Second, it’s an extremely rare case where racial biases actually protected the population being discriminated against.”

A crackdown in recent years has reduced opioid prescribing over all, “and the racial/ethnic gap in opioid prescribing has narrowed,” said Mr. Kiang, but he said it was unclear whether the gap had closed entirely.

In recent years, drug overdoses have risen sharply among black Americans, particularly among older heroin users in places where fentanyl has become widespread. One reason that the death rates from heroin and fentanyl have converged between black and white people may be simple: Heroin and fentanyl are readily available outside the health system, so they’re less affected by bias within it.

The public response to drug epidemics also tends to diverge along racial lines. During the crack epidemic, there was a greater emphasis on punishment and incarceration. With the opioid crisis primarily affecting white people, there has been more emphasis on empathy and rehabilitation. (This same disparity was seen in crack versus powder cocaine.) Race played an obvious role in the policy response, Dr. Kolodny said: “From ‘Arrest our way out of it’ to, ‘It’s a disease.’”

The response to drug epidemics also cuts along class lines, said Dr. M. Norman Oliver, Virginia’s health commissioner. “At the beginning, the opioid epidemic was centered in rural Appalachia, and as long as it involved poor rural whites, it did not get much attention,” he said. “When those prescription opioids hit the more affluent white suburbs around big cities, that’s when people started paying attention.”

Race-based physiological myths have long influenced medical practice, he said. Even today, some doctors believe that African-Americans are more tolerant of pain. One study found that relative to other racial groups, physicians are twice as likely to underestimate black patients’ pain.

Several years ago, researchers at the University of Virginia, including Dr. Oliver, probed the beliefs of 222 white medical students and residents and published results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. Half held false physiological beliefs about African-Americans. Nearly 60 percent thought their skins were thicker, and 12 percent thought their nerve endings were less sensitive than those of white people.

The medical students and residents who endorsed false beliefs like these were more likely to rate the pain of a black patient as less severe than that of an otherwise identical white patient and less likely to recommend treating black patients’ pain.

Other studies show that physicians, white ones in particular, implicitly prefer white patients, falsely viewing them as more intelligent and more likely to follow professional advice.

In 2013, the American Medical Association — the largest medical association in the United States — published a review of the relationship between pain and ethnicity in its Journal of Ethics. It concluded that variations in treatment stem in part from racial misconceptions about heightened pain tolerance among African-Americans and from the (false) notion that blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to abuse drugs.

In turn, nonwhite patients receive less pain treatment, just as there are discrepancies in how they are treated for heart disease, cancer, diabetes, kidney disease, among many other illnesses.

Dr. Oliver said the bias problem in medicine was “not intractable — I’m actually hopeful that we can change the way people think.”

He is African-American and said he was old enough to remember when racism was commonly overt and direct. “It’s primarily unconscious biases today,” he said, but he didn’t want to minimize those biases either. “They can lead to death.”

It’s a bias that is overwhelmingly harmful to minority patients, even as it may have spared some from the worst outcomes of the early opioid epidemic.