Gilbert Benavidez is a Policy Analyst with Boston University’s School of Public Health. He tweets at @GBinsolidarity. A slightly earlier version of this piece is cross-posted on The Health Care Blog. Research for this piece was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced that Medicare Advantage (MA) plans could, in 2019, expand the health-related benefits they offer. In the announcement CMS wrote that it would

allow supplemental benefits if they compensate for physical impairments, diminish the impact of injuries or health conditions, and/or reduce avoidable emergency room utilization.

Such supplemental benefits could include things that are not normally thought of as “health care,” like, for example, groceries, air conditioners for beneficiaries with asthma, and even provider organized Lyft and Uber rides to and from and medical appointments.

While MA covers all Medicare services, MA plans are already permitted to offer extra coverage for supplemental benefits. Previously, MA supplemental benefits had to have a primary purpose of preventing, curing, or diminishing an illness. This generally ruled out those that might affect health outside the traditional health system, like groceries and non-ambulance transportation. CMS’s new regulation will permit such nontraditional MA benefits so long as they “increase health and improve quality of life.”*

You may question why health care plans would include these types of benefits. The answer: If health is a puzzle, medical care is only one piece. The rest of the puzzle is filled in with pieces like environment, diet, and socio-economic status. CMS’s new regulation is intended to more directly address these social determinants of health.

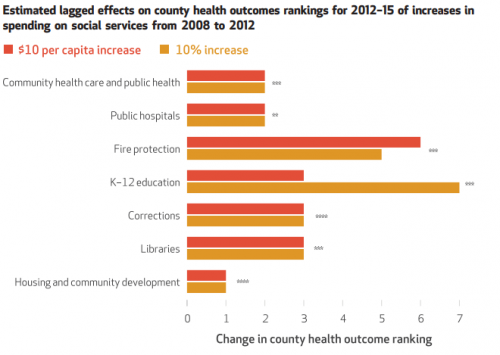

McCullough and Leider argued in Health Affairs for more aggressive action to address social determinants. Their Exhibit 3, reproduced below, demonstrates the degree to which spending in some non-health areas is associated with improvements in county health rankings. Some non-health investments are associated with bigger improvements than those more directly related to health. Investments in education, for example, are associated with bigger returns than those in public hospitals or community health care.

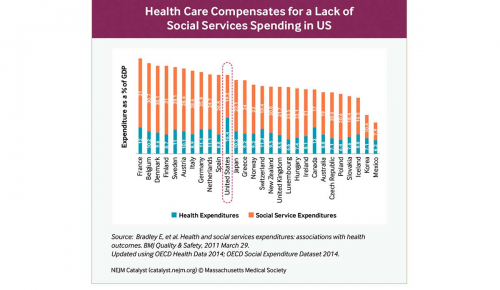

The United States may be under-spending on social services. The following graphic from Bradley, et al. juxtaposed health care spending and social service expenditure across 28 countries. Doing so reveals not just that the US spends the most on health care, which is well known, but that our spending on social services is relatively low. Most countries spend more on social services than health care, while the US spends about the same in both areas. We also know that health outcomes are generally not superior in the US, relative to other wealthy nations.

Taken together, these studies and facts suggest that the biggest health gains for the buck may not be found with additional spending directly on health care. It is possible that, at least for some US populations, providing assistance related to social determinants offers greater benefits. CMS’s regulation is an opportunity to further test this hypothesis in MA. The bet is that preventing or addressing health issues with these health-related (but not directly health care) benefits is more cost-effective than other ways to spend additional health care dollars.

There is some evidence to support this notion. An air conditioner may significantly reduce asthma symptoms. Substituting Lyft or Uber for costly ambulance rides (when appropriate) is a clear money saver and may also help remove transportation barriers as one reason people don’t show up to their appointments.

Geisinger’s “Fresh Food Pharmacy” is improving the lives of some diabetics. Diabetes affects more than 100 million Americans. Diet is instrumental to diabetes management and can decrease diabetes-associated cardiovascular risk. By improving diet, the aim of the Fresh Food Pharmacy is to cut down on costs and adverse outcomes associated with diet-related disease.

Though non-traditional benefits can improve health and reduce spending for patients, insurers might use them for other purposes. They might provide benefits that merely help market their products or that attract better risks. That’s a very real concern, particularly if plans use public funds in these ways to help themselves make a buck. As MA plans are permitted to use a portion of public dollars for additional benefits, we should be on the lookout for this kind of behavior in MA.

Naturally, even though an intervention to address social determinants can be cost-saving for specific patients, if provided widely it may not be cost-saving overall. However, it can still be more cost-effective than traditional health care. There’s no good reason not to do the most we can with each dollar we spend.

* UPDATE: A reader pointed out that UnitedHealthcare Senior Care Options (HMO SNP) currently has a transportation benefit. Perhaps some other plans do as well. But, by and large, plans don’t offer benefits to address social determinants. Because CMS is going to pay MA plans 3.4% more (as reported) to cover such expanded benefits, these types of services will be found in more plans going forward.