This is a guest post by David Anderson, a research associate at the Duke-Robert J. Margolis, MD, Center for Health Policy. You can follow him on Twitter at @bjdickmayhew and read his other work at the Balloon Juice blog.

In 2020 and beyond, under the Senate’s BCRA, the working poor will have a very hard time finding primary care providers (PCP) who will schedule appointments with them. Providers, rightly, fear bad debt from high deductible plans. They will discriminate on the ability to pay upfront.

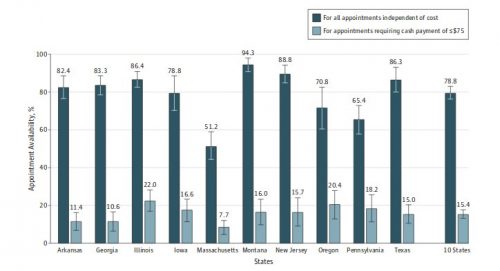

In the NEJM, Karin Rhodes, Genevieve Kenney, and Ari Friedman† looked at PCP appointment availability in the from the end of 2012 to Spring 2013. They found that appointments were usually quickly available if the person had insurance and unavailable if they were cash paying patients who could not afford the median price of services.**

The overall rate of new patient appointments for the uninsured was 78.8% with full cash payment at the time of the appointment (Figure 2). The median cost of a new patient primary care visit was $120, but costs varied across the states, as indicated in the figure legend. Only 15.4% of uninsured callers received an appointment that required payment of $75 or less at the time of the visit, because few offices had low-cost appointments and only one-fifth of practices allowed flexible payment arrangements for uninsured patients.

Why does this matter in the BCRA environment?

The baseline plan will be a plan with a $7,500 deductible for a single person. For people with means, paying $120 for a PCP visit is unpleasant but not onerous. If I had to do that this afternoon, I would grumble as I pull out a credit card. I would pay that credit card off tomorrow after I got the transaction points. Not everyone can do that.

Craig Garthwaite raises a good point this morning:

You’re worried about providers not accepting Mcaid. But who will continue to treat those unable to pay for their in-deductible care? (3/4)

ó Craig Garthwaite (@C_Garthwaite) June 23, 2017

Primary care providers will seek to minimize their net bad debt.

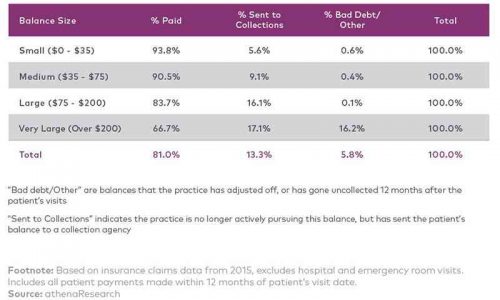

Michael Chernew and Jonathan Bush looked at how bad debt accumulates as a function of out of pocket expenses at professional offices.

The median PCP cash visit price is a large payment in the Chernew/Bush schema. Most of it will be paid as people with means take out their credit card, their HRA debit card, or their HSA card and swipe it through the machine. But a simple PCP visit will produce significant chasing and write-downs. The study is limited as it only looked at people who were commercially insured. It excludes most low income people who are in the Medicaid gap on an income qualification basis by design. The average income in the study group is highly likely to be higher than the income of people who would move from Medicaid to benchmark plans. Even so, there is significant chasing and write downs. I would predict that applying 100% first dollar obligations on people with even less income than the study population will lead to more provider bad debt. This is because these programs are income qualified and if a person income qualifies for these programs, they probably don’t have a spare $120 floating around or easy access to cheap, revolving credit.

If we assume that some normal PCP visits will include some extra services that increase the contracted payment rate to $200 or more (very large obligations in Chernew/Bush) significant sums will be written down and off. For provider practice viability concerns, providers will very aggressively screen against people with very high deductible insurance who can’t pay the entire amount of the contracted rate price up front at the receptionist desk. This is a very patient unfriendly system.

Most payment reform models focus on delivering more primary care. The objective is to substitute cheap primary care for expensive specialist, inpatient hospital stays and post-acute rehabilitation. This is the concept behind value based payment. VBID is supposed to encourage the routine, low cost, regular maintenance of chronic conditions in outpatient or community settings instead of having people end up in the hospital for preventable admissions.

Yet, under the very understandable incentives of primary care physicians wanting to stay in business, access to primary care for the working poor who would have several thousand dollar deductibles that apply to all services, will be greatly restricted because of the cost barrier. If we want all members of our shared society to have decent health and decent lives, should want people to have easy and ready access to primary care. This bill creates strong business incentives to create barriers to primary care access.

**†Rhodes, K. V., Kenney, G., & Friedman, A. (2014). Primary Care Access for New Patients on the Eve of Health Care Reform. JAMA Internal Medicine. Retrieved June 23, 2017.