This post is part of a series in which I’m dedicating a month to learning about twelve new things this year. The full schedule can be found here. This is month two. (tl;dr at the bottom of this post)

February turned out to be just as valuable as January, with one caveat. It’s clear that my education in wine will need to go on far, far longer than that in water management. What I did learn, however, gave me a much great appreciation for wine, and it’s made me much more likely to try wine and order it in the future.

The most impressive thing about wine, and something that I somewhat ignored before, is how much variety people can get out of one ingredient. Almost all wine is pretty much just grape juice that’s been fermented. That’s all. It’s not like they add in tons of other additives. And from this one fruit, winemakers are able to create a ridiculous numbers of flavors and tastes.

The first book I read was Drink This: Wine Made Simple, by Dara Moskowitz Grumdahl. A perfect first choice. If you’re going to buy one book on wine, this is the one I’d get. According to Dara, all wine should be considered by its “holy trinity”:

The first book I read was Drink This: Wine Made Simple, by Dara Moskowitz Grumdahl. A perfect first choice. If you’re going to buy one book on wine, this is the one I’d get. According to Dara, all wine should be considered by its “holy trinity”:

- The type of grape

- Where the grapes were grown

- How the grapes were turned into wine

The first is clearly a big deal. Dana discussed seven of the many varietals of grapes in her book, and I feel like if I mastered those, I’d be ahead of most people. She has chapters on Zinfandel, Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling, Chardonnay, Carbernet Sauvignon, Syrah, Sangiovese, Terpranillo, and Pinot Noir. What I didn’t know was that all grapes pretty much put out white juice; it’s allowing them to sit with their skins that makes wine red. So the type of grape will be a major component of flavor.

Where the grapes are grown (fancily termed terroir) is also a big deal. The temperature and rain matters. Evidently you don’t want your grapes to get too big or the wine is watery crap. You also want grapes to struggle. Making the vines miserable seems to make the resulting grape and wine better. What’s in the soil? Is it limetone? Clay? Minerally? All this matters as well. Grapes grown on slopes in valleys are often the best because they have to work hard to get water and see the sun. There are some amazing anecdotes of workers shoveling the dirt in valleys back up the slopes of vinyards after rainstorms because that “terroir” is so valuable.

I’d roll my eyes at a lot of this if I wasn’t already such a fan of scotch. I completely believe I can taste the sea-salty air in a glass of 12-year-old Caol Ila, and the peat of a 10-year-old Laphroaig is unmistakable, so I have no difficulty believing that the area where the stuff is made is important.

Finally, there are the post-picking steps that matter. Did the grape sit with the skins (red)? Did they age it in a barrel (which imparts flavor and tannins)? Was the barrel “toasted”? Was it a new barrel or an old one? Did they allow malolactic fermentation to occur (which changes malic acid to lactic acid, and gives Chardonnay its buttery flavor)? Did the wine sit “on the lees” which means resting with dead yeast and some grape solids? The Germans evidently add in grape juice to their Reisling to make it sweet, which is probably why my wife likes that best.

Understanding these three things gets you far. Dana also runs you through tasting exercises to get you to tell the difference between the major types of each varietal. It’s ambitious, and I didn’t do it. At least, not this month.

I next read True Taste: The Seven Essential Wine Words by Matt Kramer. It’s short, and I didn’t feel like I learned anything more than what I’d already gleaned from Drink This. I can’t recommend it as highly. Based on reader recommendation, I also picked up The Oxford Companion to Wine. Holy crap, people. Who needs to own that? It’s like the most ridiculously thorough wine dictionary ever. I imagine the sommelier at Per Se might need to have this handy, but not many others. This is not a book you read cover to cover.

At this point, I stopped to watch two movies that you guys recommended. The first was Somm, and you can stream it on Netflix. It’s documentary that follows a few talented Jedi Knights of wine around on their quest to make it onto the Jedi Council of wine. Something like 200 people in the history of the world have passed the test. There’s a written component, for which you clearly need to buy and memorize The Oxford Companion to Wine; there’s also a tasting component where you need to identify six wines, three red and three white, to an insane level of specificity. No one on Earth needs to pass this test. But the four guys the movie follows try to, and I won’t spoil what happens. Needless to say, I didn’t feel good about any of them, no matter what their test results were.

I also watched Sideways, which I hadn’t seen before. Great movie. Wine was incidental, but clearly the guy who wrote the book and screenplay had read many of the books I did, too. We have the same factoids at hand.

Next I read Kevin Zraly’s Windows on the World Complete Wine Course. This is the book you want to read if your goal is to impress your friends and waiters. Like Dana, Kevin goes by types of wines. But instead of explaining more of the mechanics, he lists the regions, wineries, and major players in each area. I imagine this is the book you study to become a Jedi Knight of Wine. I have none of the bottles he talks about in my house, although many of my friends and brother do. If you’re committed to being a real wine person, this is a book you should get and read multiple times.

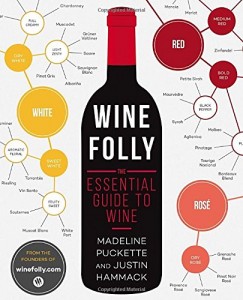

Finally, I read Wine Folly: The Essential Guide to Wine by Madeline Puckette Justin Hammack. If you want to own one book on wine, this is the one to buy. I think it’s based on their very popular website. It’s more of a resource book than a learning book, with much more detail on way more wines than Drink This. Every time I wanted to try a new wine, this is the book I turned to first. Nowhere near the insane detail of The Oxford Companion, but lots of good info on nearly any wine you’d find. It has suggestions on food pairings, where wines are made, and more.

Finally, I read Wine Folly: The Essential Guide to Wine by Madeline Puckette Justin Hammack. If you want to own one book on wine, this is the one to buy. I think it’s based on their very popular website. It’s more of a resource book than a learning book, with much more detail on way more wines than Drink This. Every time I wanted to try a new wine, this is the book I turned to first. Nowhere near the insane detail of The Oxford Companion, but lots of good info on nearly any wine you’d find. It has suggestions on food pairings, where wines are made, and more.

I also read many, many articles and papers you sent me on how wine is a scam and you shouldn’t believe anyone about it.

I disagree.

It’s clear that some wine is expensive only because people think it is, and because it’s a limited resource with great demand. But the reasons for some wine being expensive are obvious. Was the quality of grape high? That’s a cost. Was it picked by hand and carefully tended (like Pinot Noir must be)? That’s a cost. Was it aged in barrels for years? That’s a cost. Was it carefully blended, managed, transported, etc? That’s a cost.

Now that won’t get you to hundreds of dollars a bottle, but it will get you to tens of dollars. You won’t find all of the above in an $8 bottle of wine.

But – and this is important – that doesn’t mean you can’t like cheap wine. What nearly every author stressed was that you like the wine you like. If that’s $10 Reisling (like my wife), so be it. I found that I liked Oregon Pinot Noir more than Washington State Pinot Noir.

February wine learning continues. I have learned I like Oregon Pinot Noir more than California. pic.twitter.com/2fzxQwi25u

— Aaron E. Carroll (@aaronecarroll) February 18, 2016

I liked a Cabernet from Napa even better. But my favorite bottle of wine this month was a French Bordeaux that was 75% Merlot and 25% Cabernet Franc, and was nowhere near the most expensive I opened. I don’t care what you (or Miles Raymond) thinks of it. It’s what I liked.

I think wine aficionados get into trouble when the operationalize “good” and tell you what you should or shouldn’t prefer. No book I read endorsed that.

The most important thing I learned was that I should get out there and sample more wines. There are likely many others I’ll love, some expensive and some cheap, but I’ll never know until I try.

tl;dr: Read Drink This: Wine Made Simple and buy Wine Folly as a reference to have around.