The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s Study of the Central Intelligence Agency ‘s Detention and Interrogation Program showed in ghastly detail that physicians and psychologists participated in the torture of prisoners. In response, I wrote a post documenting how the ethical codes of physicians and psychologists unanimously and absolutely forbid participation in torture. Some readers responded with arguments for why torture is often or sometimes justified, which is the view held by a majority of Americans. In this post, I’ll try to explain why medicine and (my profession) psychology must take an absolute stand against participation in torture.

In response to the Senate Report, the President of the AMA, Dr. Robert Wah, wrote that

the AMA’s Code of Medical Ethics and the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Tokyo… forcefully state medicine’s opposition to torture or coercive interrogation and prohibit physician participation in such activities. The physician’s most important role is that of healer, and that role is seriously compromised in situations of torture and coercive interrogation.

The key to understanding why physicians and psychologists cannot torture is to understand what Dr. Wah said about the role of a healer. Being a clinician is more than simply having knowledge about treatments for disorders of the body or mind. Healing is also an interpersonal relationship. Francis Peabody wrote

There are moments, of course, in cases of serious illness when you will think solely of the disease and its treatment; but when the corner is turned and the immediate crisis is passed, you must give your attention to the patient… The good physician knows his patients through and through, and his knowledge is bought dearly. Time, sympathy and understanding must be lavishly dispensed, but the reward is to be found in that personal bond which forms the greatest satisfaction of the practice of medicine. One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.

As patients, we have strong expectations about the character and motivations of the doctors who treat us. We expect them to be devoted to relieving our suffering, that they will respect our rights to control our bodies, and that our healers will not exploit us to their own advantage. Finally, we want our healers to treat us in ways that accord with our values, even when the healer does not share our values.

To be a healer is not just to master a therapeutic technology. It’s also a matter of character, of your disposition to behave virtuously. Healers are compassionate. They respect patients’ autonomy and are zealous for their wellbeing. Becoming a healer should involve not just learning technical skills, but also cultivating your emotional being so that you care for patients in the proper way.

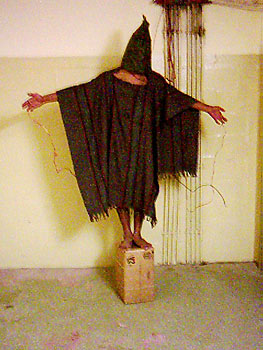

Torture is the antithesis of healing. To torture is to deliberately cause unendurable suffering to either extract information or – let’s be honest about it – to terrify others in the victim’s community. Rather than respecting the autonomy of the patient, torture is an assault on a defenseless prisoner. This assault may be inescapable. When the purpose of torture is to extract information, the prisoner who does not have that information has no recourse: how can you prove that you do not know what you do not know? Rather than valuing the patient as an end in himself, torture completely subordinates the wellbeing of the prisoner to the ends of the torturer.

We cultivate a virtuous character by practicing virtue. Conversely, practices like torture build a vicious character incompatible with the role of a healer. We see this in the histories of the Nazi doctors, the Stanford Prison Experiment, and everyone’s experience of the character of bullies: if you practice brutality and sadism, you may acquire a taste for it. Moreover, those who practice cruelty develop not only the habit but also a skein of rationalizations to justify it.

Torture should therefore be wholly repugnant to members of the healing professions. The public should be able to trust that its healers are, in their guts and at their cores, incapable of this behavior. Leaders in medicine and psychology recognize that torture is not just wrong but also morally corrupting. This is why medical and psychological societies absolutely ban participation in torture.