The following originally appeared at The Upshot (copyright 2014, The New York Times Company). See also this, related post that reinforces my point.

It’s a rare health policy wonk who has a good word to say about Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate formula. That’s the formula created by Congress to govern the amount that Medicare pays to physicians for various treatments. It is supposed to adjust payments to meet an overall spending target tied to economic growth.

But it hardly ever works out this way. Congress routinely overrides the cuts that the formula would demand, and it did so again a few weeks ago. Health care experts often view such action as a failure of government to control health care costs. But that view is incomplete. Congressional overrides of the formula have been fiscally responsible for the most part. And, apart from one gimmick, the most recent “doc fix”—as changes to the formula are known—is as well.

Medical spending, including that by Medicare, typically grows faster than the economy, and often significantly faster. The formula, often called the S.G.R., is intended to bring Medicare spending and economic growth into alignment, which necessarily demands spending cuts. Congress, wary of making such cuts, overrides them year after year, creating an ever-growing gap between Medicare’s payments to physicians and the level dictated by the formula. The gap now stands at about 24 percent. Good luck getting physicians to keep Medicare patients if the payments are suddenly cut 24 percent.

However, from another point of view, the formula—as flawed as it is—has helped keep Medicare spending lower than it might otherwise have been. Instead of cutting physician payments by the large amount the S.G.R. demands, Congress has increased payment rates, but typically by only tiny amounts—at an annual rate of just 0.7 percent. That pace does not keep up with the typical cost of care.

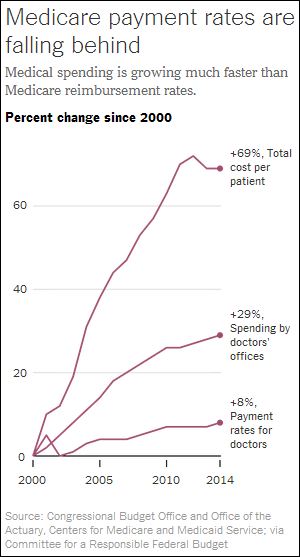

The gap can be seen in the accompanying chart. The bottom line illustrates how Congress has permitted Medicare physician payments to grow. The middle line shows an index of medical spending—spending at a typical physician’s practice over time—that is a proxy for the change in price for a typical, or average, medical treatment.

This index, however, doesn’t come close to capturing all of Medicare’s costs. Apart from the cost growth of a given treatment, the number of treatments and the intensity of those treatments have also grown over time. You can see the total growth in spending per patient, combining all these factors in the top line. Many analysts point to the growth in volume and treatment intensity as evidence that the fee-for-service nature of Medicare’s payment system—so that doing more procedures increases costs without necessarily providing better care—is deeply flawed.

The relatively gentle increases in Medicare payment rates makes clear that the formula is not the problem. I think that the formula has actually helped Congress be more fiscally responsible than it otherwise might have been. To physicians who fear a double-digit decrease in payment rates called for by the formula, a 0.5 percent or a 1.5 percent increase that Congress passes looks like a great deal.

To be sure, the way Medicare pays physicians has its problems. But in a world in which nothing in health policy seems to work as intended, we should take some solace in such small victories.