Links to all posts in the series to which this post belongs are in the introductory post.

From this series’ review of the job lock literature and Nicholas Bagley’s review of the relevant legal landscape, as well as how the ACA changes it, I draw the following conclusions:

- There’s strong theoretical reason to expect some job lock, but the theory can’t tell us how big an effect it has on the labor market.

- Job lock exists because of the legal and regulatory structure we’ve chosen to impose on the health insurance and labor markets.

- With near unanimity, the empirical literature has found evidence that employer-sponsored health insurance reduces the likelihood of retirement. This is consistent with one form of job lock. However, it is worth keeping in mind that people also don’t retire because health benefits, like wages, are a form of compensation. The job lock effect and the compensation effect are different, though potentially confounded in some studies.

- There is also strong evidence that employer-sponsored health insurance increases the labor force participation of prime-aged workers, while spousal coverage reduces it. Moreover, sicker individuals are more likely to work more at jobs that provide their source of coverage. Such results are consistent with job lock.

- Studies are more mixed on the effect of employer-sponsored health insurance on job mobility (as distinct from labor force participation), but the balance of results in the literature are consistent with this form of job lock.

- Entrepreneurship lock—that individuals are less likely to elect to become self-employed because of the greater value of employer-sponsored health insurance relative to what they can access on the individual market—is another variant of job lock identified in the literature. Here too, the vast majority of studies find evidence consistent with it.

- In several ways the ACA will mitigate job and entrepreneurship lock.

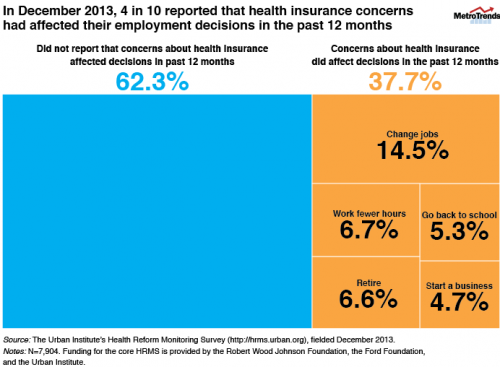

Finally, here’s a bonus bit of survey evidence from the Urban Institute:

To all this, consider the following additional considerations and caveats: Each estimate of job lock only pertains to one type (labor force participation, job mobility, entrepreneurship lock) and, usually, to a subset of the population for whom it might be relevant. As such, no single estimate is comprehensive of the entire phenomenon. Moreover, for cases for which there are multiple, comparable estimates, nobody has done a meta-analysis. Consequently, it is not clear what is the “right” point estimate for each variant of job lock. Nor is it clear what the overall labor market effects are, quantitatively and precisely.

The ACA only addresses certain, but not all, conditions that give rise to job lock and not completely. If you combine this fact with the prior paragraph, you’ll notice that we have a situation in which we neither fully know the extent of the problem nor the extent to which the ACA will address it. In their 2002 literature review, Gruber and Madrian also commented on the fact that we do not know the full welfare implications of job lock. As best I can tell, the literature has not advanced in this regard since their review.

Nevertheless, the labor market distortions of the pre-ACA insurance landscape (some of which remain) are real. They weighed heavily on the minds of economists and, to some extent, motivated some of the provisions of the health reform law.