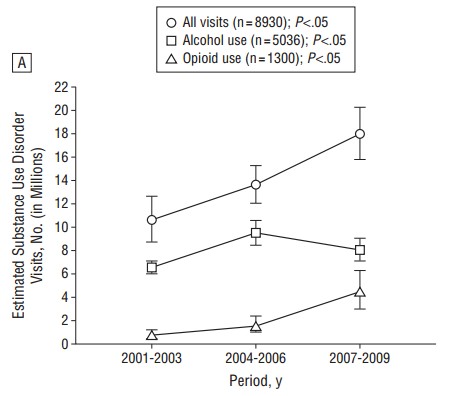

Analyzing nationally representative data on ambulatory visits, Joseph Frank, John Ayanian, and Jeffrey Linder (Archives of Internal Medicine, 2012) illustrated the recent growth in opioid use, in both absolute terms and as a proportion of those with diagnosed substance use disorders (SUDs). A large minority (36%) of SUD patients go untreated by either pharmacological or psychosocial therapeutic means.

Opioid use growth is facilitated by the health system. In NEJM last week, Anna Lembke wrote,

Sixty percent of the opioids that are abused are obtained directly or indirectly through a physician’s prescription. In many instances, doctors are fully aware that their patients are abusing these medications or diverting them to others for nonmedical use, but they prescribe them anyway. Why?

Among the reasons she provided are: “[t]he ‘all suffering is avoidable’ ethos” and that “it is faster and pays better to diagnose pain and prescribe an opioid than to diagnose and treat addiction.” She concluded,

[T]he problem of doctors prescribing addictive analgesics to patients with known or suspected addiction will be solved only when the threat of public and legal censure for not treating addiction is equal to that for not treating pain and when treating addiction is financially compensated on a par with care for other illnesses. The former will occur only when addiction is considered a disease by medicine and society, for only then will it be treated as a legitimate object of clinical attention. The latter will occur only when time spent with patients is valued as much as prescriptions and procedures.