My friends are all aflutter about the news that drinking alcohol – pretty much any alcohol – increases the risk of breast cancer:

Context Multiple studies have linked alcohol consumption to breast cancer risk, but the risk of lower levels of consumption has not been well quantified. In addition, the role of drinking patterns (ie, frequency of drinking and “binge” drinking) and consumption at different times of adult life are not well understood.

Objective To evaluate the association of breast cancer with alcohol consumption during adult life, including quantity, frequency, and age at consumption.

Design, Setting, and Participants Prospective observational study of 105 986 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study followed up from 1980 until 2008 with an early adult alcohol assessment and 8 updated alcohol assessments.

Main Outcome Measures Relative risks of developing invasive breast cancer.

Deep breath, people. This is a study that followed a whole lot of nurses for almost 30 years, checking in every once in a while to see who developed breast cancer and who was drinking alcohol. They controlled for lots of other things that could cause breast cancer. Over the study period (a whopping 2.4 million person years), there were 7960 cases of invasive breast cancer.

The news that has everyone getting upset is that alcohol consumption was significantly associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Drinking 3-6 alcoholic drinks a week increased the risk of getting breast cancer by 15% compared to women who never drank alcohol. Drinking 2 alcoholic drinks a day increased the risk of getting breast breast cancer by 51% over not drinking at all. It didn’t matter what kind of alcohol they drank; it was all bad.

Before you panic, remember that this study isn’t perfect. It wasn’t a controlled trial, so you can’t prove causality. It relied on past recollections, which are subject to recall bias. Moreover, there’s nothing in this study which says that changing your drinking habits will change your risk. Even so, let’s assume the results are real. What the authors report, and I cite above, are relative increases in risk. They don’t refer to the absolute risk.

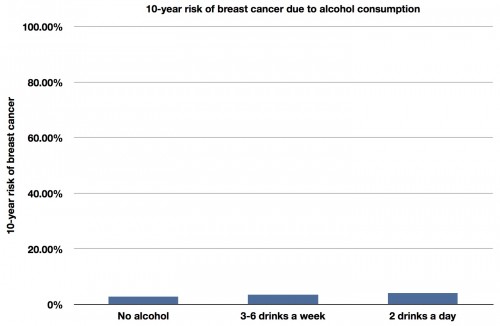

What’s the difference? Well, the risk of developing breast cancer for an average woman over a ten year period is 2.8%. This means that drinking 3-6 drinks a week raises the ten year risk to 3.5%. Drinking two alcoholic drinks a day raises it to 4.1%. Here’s another way of looking at that:

Doesn’t look as scary does it?

The accompanying editorial notes that many women will need to weigh the risks and benefits of modest alcohol consumption. After all, studies have shown that moderate drinking can reduce the risk of heart disease. Therefore, increases/decreases in breast cancer may be balanced out by decreases/increases in heart disease.

Not as clear anymore, is it?

But there’s another layer than many in the media are missing. A lot of people like to drink every now and then. They enjoy an ice cold beer at a summer barbecue. They relish a good bottle of wine at a birthday dinner with family. They reminisce about a single malt scotch shared with with friends on a crisp autumn night. For some of these people, the pleasure derived from something they enjoy may be worth the small increase in the risk of breast cancer that results.

I can hear the howls of protest already. But here’s the example I always go to: the number one killer of children in the US is car accidents. But we don’t ever consider stopping driving. I know that every time I put my kids in a car, I’m significantly increasing the chance that they could die. But I (and pretty much all of you) believe that the benefit to our lives from cars outweighs the increased risk of death in our children. Let me put it another way. We all accept that it’s worth a number of children dying so that we can all get around more easily.

I’m not condemning automobiles. Nor am I judging anyone for using them. I just want us all to be able to acknowledge that the world is a complex place, and one in which it is OK to trade off some benefits and harms. You may want to do anything in your power to reduce the risk of getting breast cancer, no matter how small the difference. But others may not. They may believe a small risk reduction isn’t worth the changes in their own personal quality of life.

Unless we’re all ready to stop driving completely, we should tolerate those decisions.