This blog pumps out a lot of facts and data. When we discuss policy, we are evidence based.* We strive to educate and illuminate. It’d be lovely, if naive (as it turns out), to believe that our efforts play a role–even if a small one–in achieving consensus for better policy. Heck, it’d be great to believe facts and information did that in general, even if not provided by TIE. But we can’t just trust that’s what happens. That’s not the TIE way. We have to look for evidence. What does information do?

The evidence is not good. Perhaps the best that can be said is that information about policies does matter. Policy information matters at least as much as cues from the leadership of the political parties. John Bullock conducted two randomized experiments that demonstrated these facts. In a paper titled Elite Influence on Public Opinion in an Informed Electorate (pdf; American Political Science Review, August 2011), here’s what he wrote about his results,

The normative case for democracy loses much of its force if citizens arrive at their political views unthinkingly […]. Many scholars fear that citizens are doing just this—mechanically adopting the positions of their party leaders even when they have other information on which to base their judgments […]. But examining this concern entails isolating the effects of both policy information and position-taking by party elites. Few studies have done this, and their implications have not been clear. The experiments presented here do isolate the effects of party cues and policy, and they suggest an important condition under which the concern does not hold. Party cues are influential, but partisans in these experiments are generally affected at least as much—and sometimes much more—by exposure to substantial amounts of policy information.(Bold mine)

Given the nature of Bullock’s experiments (the paper is ungated so you can read about them yourself), his conclusions are strong. Policy information matters. Those who seek it out are affected by it. Hence, TIE has the potential to matter too, even if only a tiny bit. Case closed. Pop the corks.

But wait. Though information matters, that is not the same thing as saying it leads toward consensus or even better policy. Maybe it matters in the sense that it tends to polarize. Based on far less rigorous techniques than Bullock’s experiments, additional evidence suggests that information could do just that.

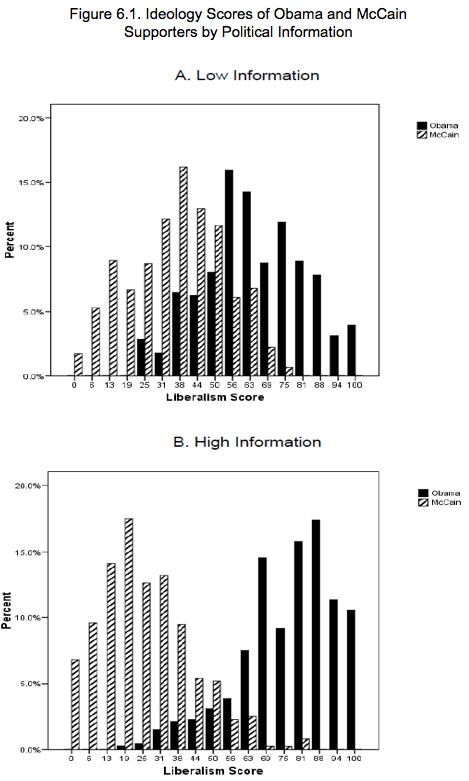

I saw the following two-part chart posted on Matt Yglesias’s blog. It’s from Alan Abramowitz’s book The Disappearing Center, which I have not read. Yglesias explained, “The implication [from the charts] is that the existence of a large bloc of crossover voters is driven by the existence of a large bloc of people who don’t actually know anything about politics.” Add information and voters sort themselves into camps. The center disappears.

Is information polarizing? The charts above suggest that political information might be. That’s not the same thing as saying policy information is. Also, maybe information is not the cause of polarization. Maybe those who strongly identify with one party or another seek out information to support their cause. In other words, maybe polarization is already there, and it motivates information seeking.

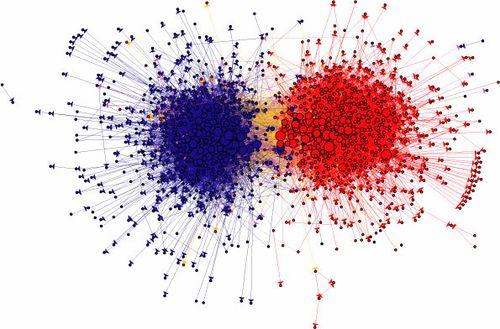

There is evidence that people seek out information consistent with their world views. In doing so, they are less exposed to new ideas that do not comport with their ideology. This is no more evident than in the blogosphere. The chart below, from a paper (pdf) by Lada Adamic and Natalie Glance, “is a network analysis of linking patterns among conservative and liberal political blogs. The tight clustering suggests that many of these writers are simply echoing each other” (quote from Bill Gardner).

All of this suggests that information is useful to people, not for building consensus, but as a cudgel and as a way to signal ideological affinity and affiliation. We may not be seeking information to arrive at truth or goodness, but to score debating points. As Patricia Cohen reported in the New York Times, reason itself may have evolved to win arguments.

“Reasoning doesn’t have this function of helping us to get better beliefs and make better decisions,” said Hugo Mercier, who is a co-author of the journal article, with Dan Sperber. “It was a purely social phenomenon. It evolved to help us convince others and to be careful when others try to convince us.” Truth and accuracy were beside the point.

So, where does this leave TIE and, more broadly, the quest for evidence-based policy? Should we just stop trying?

No. Expecting truth to be valued by all and evidence to always convince are high bars, too high. Yet evidence can still influence policy and, depending on your perspective, improve it. That even occurs for aspects of policy that are extremely controversial. Take the individual mandate, for example. Whether you’re for it or against it, you are likely to agree that it or something like it is central to the success of the ACA’s health insurance market reforms. It’s purpose is to create a market in which guaranteed issue and the ban of pre-existing condition exclusions can succeed. If healthy people don’t have an incentive to purchase coverage, only sick ones will, leading to higher premiums that destabilize the market and make it more difficult for people to insure against the risk of costly health care.

That we know all this is the result of relatively old research and experience. Still, it wasn’t something everyone involved in health care reform once knew well enough to believe an individual mandate was necessary. In 2008, then candidate Obama didn’t think so, for example. For those who believe in health reform, those who voted for the ACA, among others who want it to succeed, accepting the necessity of the individual mandate was important. To the extent that dissemination of accessible, relevant evidence did that is a reason to celebrate information.

Put another way, it’s easy to implement policy that doesn’t work. If research and evidence can at least help nudge policies toward variants more likely to fulfill their intended purposes, that’s a useful role. That not everyone agrees that those purposes are worthwhile or even to be preferred over others is not something evidence from research can do much about. That’s not its job.

* When statements not based on evidence slip in, which does happen, our good readers make sure we notice.