So now we have the unveiling of Sen. Lieberman’s and Sen. Coburn’s plan to “Save Medicare and Reduce the Debt“. Lots and lots of people like it.

It’s got plenty of cost-shifting onto the elderly, which I think is a bad idea . It totally requires the PPACA to remain in place so that 65-67 years olds can get insurance, which is ironic, since half of the “bipartisan support” wants to scrap that law. And it once again supports the idea of raising the eligibility age for Medicare.

This is a good time to cross-post my last column for CNN.com: “Life expectancy deceptive issue in Medicare debate”.

Should we control the spiraling cost of Medicare by raising its eligibility age from 65 to 67 or more? Many have argued that we should, because, they say, life expectancy today is much higher than when Medicare was created. The program was never designed to last so many years per person, and so, perhaps, people should retire later.

The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that raising the eligibility age of Medicare to 67 would save about $125 billion through 2021 alone. That sounds like a great deal. However, the CBO doesn’t say that health care costs will go down overall, or that this money won’t have to be spent by others. It will.

Those savings to the federal government are achieved mostly through cost shifting. It’s entirely possible that we might “save” that $125 billion only by shifting the cost onto the elderly, employers and others in the exchange risk pools. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that seniors age 65-67 would have to pay an additional $5.6 billion in out-of pocket costs — in 2014 alone

Let’s say you think this is OK, however. Perhaps you believe that, up until Medicare kicks in, you should be responsible for your health care costs. The question then becomes, is it reasonable to ask seniors to wait longer for Medicare because people are living so much longer?

The problem is, life expectancy is complicated. General life expectancy, or life expectancy at birth, is mostly affected by early death. Whenever a child dies, it skews life expectancy from birth way down. Anything that increases infant mortality, or care that ends a potentially devastating childhood illness (think vaccines), will increase general life expectancy a lot. Therefore, many of the gains in overall life expectancy have nothing to do with how long an elderly person lives, but how well we do in treating childhood illnesses.

What we really should care about in this case is not life expectancy at birth, but life expectancy at age 65. In other words, if you make it to 65, how long will you be on Medicare? That’s when things get tricky.

First, if you made it to 65, even back in 1950, you could expect to be on Social Security for 14 years. In 1970, if you made it to 65 and qualified for Medicare, you could expect to live for about 15 years on the program. So a lot of people were making use of these programs, for a lot of years. In 1987, you could expect about 17 years on Medicare; by 2007, almost 19 years.

Yes, life expectancy is going up. But not nearly as fast for those on Medicare as people think. An additional problem is that it’s not going up equally. A new study just released by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation looks at changes in life expectancy from 1987-2007 by county. Here’s the most troubling part of it (emphasis mine):

Change in life expectancy is so uneven that within some states there is now a decade difference between the counties with the longest lives and those with the shortest. States such as Arizona, Florida, Virginia, and Georgia have seen counties leap forward more than five years from 1987 to 2007 while nearby counties stagnate or even lose years of life expectancy. In Arizona, Yuma County’s average life expectancy for men increased 8.5 years, nearly twice the national average, while neighboring La Paz County lost a full year of life expectancy, the steepest drop nationwide. Nationally, life expectancy increased 4.3 years for men and 2.4 years for women between 1987 and 2007.

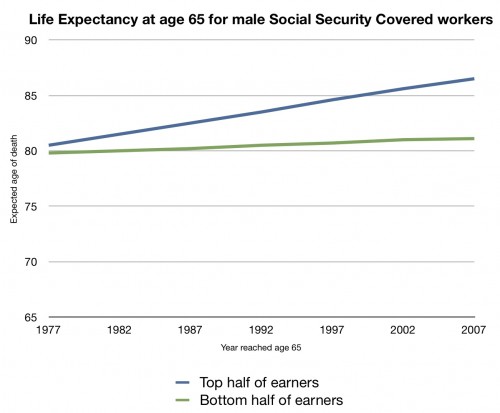

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that poorer people may not be making nearly the gains in life expectancy that wealthier people are. If you look at the maps from those studies, this seems to be true. And it’s born out by another study that appeared in Social Security Bulletin in 2007. This is a chart I made from data in that paper (Table 4):

This is the life expectancy of a covered male Social Security worker who reached age 65 in 1977-2007. The blue line is the top 50% of earners; the red line is the bottom 50%. While earners in the top half have seen an increase of their life expectancy at 65 rise about five years over these three decades, the bottom half saw their life expectancy at 65 rise barely a year.

This is what you should think about whenever someone talks about increasing the eligibility age for Medicare or Social Security. Not everyone’s life expectancy is increasing. Those who need the benefits the most would be the ones who stand to lose the biggest percentage of them by raising the eligibility age. Asking them to pay more out-of pocket doesn’t seem like a fair, nor workable, solution.