This post was jointly authored by Austin Frakt and Aaron Carroll.

By now most of the blogosphere has weighed in on Joe Lieberman’s idea of increasing Medicare eligibility from age 65 to 67 (see Frakt, Klein, Volsky, Drum, Krugman). Most of the focus has been on how the delayed eligibility will affect overall health costs. Though federal costs may go down, overall costs would not, because most would just be shifted to seniors themselves. Cost isn’t everything, though. There’s something else delay would do: harm health.

This is not guesswork on our part; there’s clear evidence in the literature. In several papers, Michael McWilliams and colleagues found that utilization, spending, and outcomes for age-eligible Medicare beneficiaries differed for those who had been uninsured prior to turning 65 vs. those who had been insured. Their work was based on survey data, sometimes merged with Medicare claims. This is a relatively strong analytic approach since it exploits a discontinuity in coverage that potentially applies to nearly all individuals: the vast majority of the population enrolls in Medicare at age 65.

The authors found that, relative to those with insurance before age 65, those without insurance prior to Medicare eligibility spent much more money on health care after they became Medicare eligible. In other words, people wait to get care until their Medicare kicks in. This is bad both for health and for the federal government’s bottom line.

Delaying Medicare even longer would likely make this worse. People would forego care longer, health would suffer, and Medicare would pay for the consequences later.

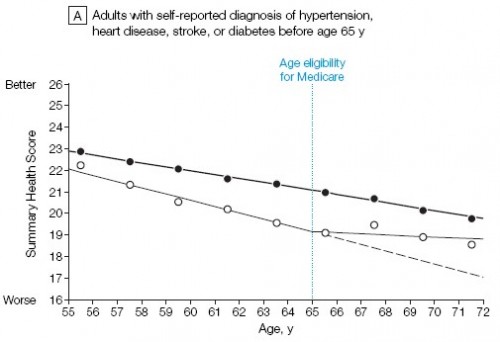

Here’s the evidence in charts, extracted from McWilliams et al.’s papers (references listed at the end). First, from [1], we see that after age 65, uninsured adults with (chart A) and without (chart B) hypertension, heart disease, stroke, or diabetes all have a significant and improved change in trend in health status after obtaining Medicare. Insured adults, however, do not experience a change in trend. Medicare improved the health of the uninsured; delaying Medicare would delay that help.

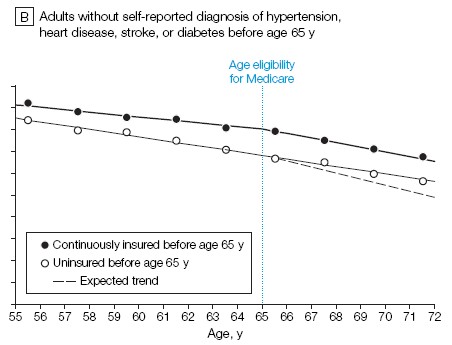

Next, from [2] we see a similar phenomenon in doctor visits. Relative to the insured, those uninsured prior to age 65 visit the doctor more after obtaining Medicare eligibility.

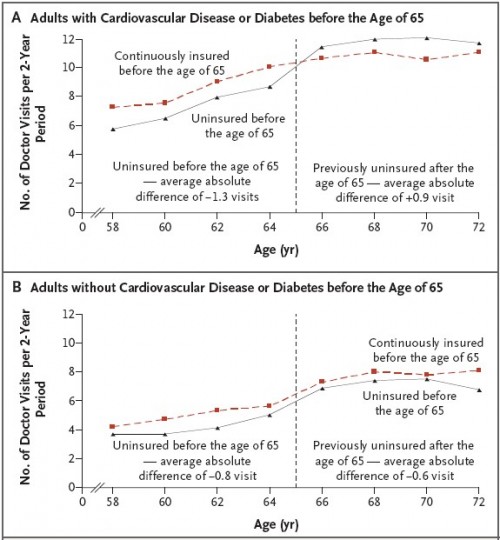

From the same paper ([2]), here are the results on hospital admissions.

This shouldn’t surprise anyone. It makes sense. It’s hard to get affordable insurance as you approach age 65. If you’re lucky enough to have insurance, then you’re getting the care you need, so getting Medicare is nice, but not a huge change in your life. If you’re uninsured, though, then getting Medicare is a huge change. If you know you need care, and it’s expensive, then you will likely try and wait until the Medicare kicks in to get it. People do this all the time; the evidence above confirms it.

Raising the eligibility age will just force these people to wait longer.* If this somehow saved us money, then we suppose you could have a debate about its benefits and harms. Knowing that it will likely cost Medicare more, however, means that it’s entirely possible that delaying Medicare eligibility will cost more and lead to worse outcomes. That’s the worst of both worlds.

* McWilliams et al.’s analysis does not take into consideration the effect of health reform. Provided it stays on the books, the non-elderly will have different options in 2014. Still, the analysis shows the value of health insurance, and in particular of universal coverage.

References

[1] McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Health of previously uninsured adults after acquiring Medicare coverage. JAMA. 2007;298:2886-94.

[2] McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Use of health services by previously uninsured Medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:143-53.