There have been a number of interesting posts today (including here) on the subject of life expectancy and its effect on entitlement programs for the elderly.

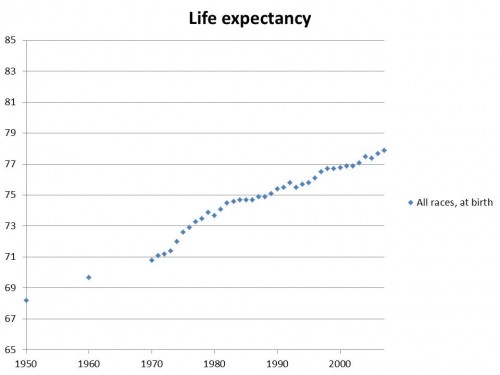

There are a number of people out there who believe that we need to increase the age at which people start getting benefits because people are living so much longer than they used to. They cite data like those below, which show life expectancy for all individuals in the US, from 1950 to 2007:

When you look at the data like this, it seems only sensible, after all. According to this, almost no one could expect to live much past 65 in 1950. Moreover, there’s been a steep climb for the past few decades. If you take this at face value, then it seems only natural that we would have to increase the age at which these programs kick in.

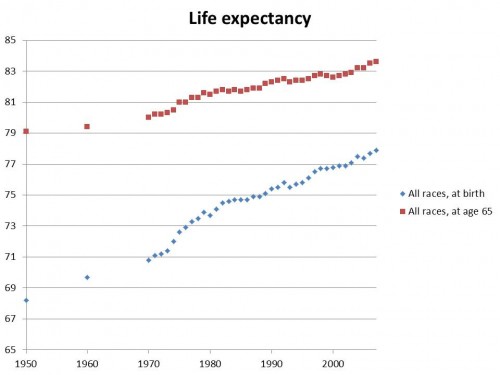

This chart is a bit deceptive, however. See, whenever a child dies, it skews life expectancy way down. Anything that increases infant mortality, or care that ends a potentially devastating childhood illness (think vaccines), will increase life expectancy a lot. What we really care about is not life expectancy at birth, but life expectancy at age 65. In other words, if you make it to 65, how long will you be on one of these programs? Let’s add that line in:

Two things to note here. First, if you made it to 65, even back in 1950, you could expect to be on Social Security for 14 years. In 1970, if you made it to 65 and qualified for Medicare, you could expect to live for about 15 years on the program. So a lot of people were making use of these programs, for a lot of years. The second thing to notice is that life expectancy for someone who lives to 65 and qualifies for these programs, hasn’t gone up as much, or as quickly, as people think.

The reason that Social Security has become more costly is not nearly as much that people are living longer on the program, as it is that many more people were born into the generation approaching 65. They aren’t getting more benefit individually; as a group there’s just more of them. When you argue that you want to raise the age at which they start to 68, instead of 65, you’re basicly giving them as many years on the program as a person who hit 65 in the mid 1970’s. That’s a pretty big change.

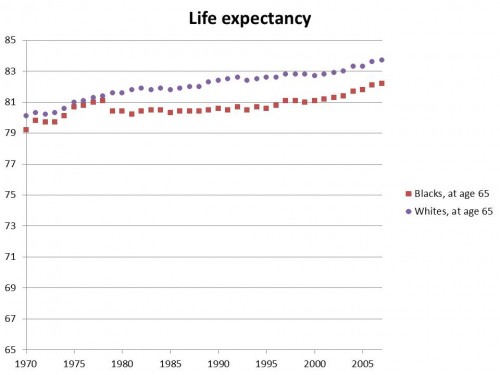

One more point. Life expectancy at age 65, which is really how many years you can hope to receive Medicare or Social Security, isn’t the same for everyone. Here it is by race:

So when you propose to raise the age at which it starts to 68, you’re depriving the average black American (fewer of whom make it to 65 already) more of his or her benefit, compared to the average white American.

Something to think about.