Since it didn’t get featured at HuffPo:

In case you’ve been under a rock, last week the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force released their updated recommendations on screening for breast cancer. The USPSTF is not a political organization. They aren’t an advocacy organization, or even a policy making organization. They are, “[a]n independent panel of experts in primary care and prevention that systematically reviews the evidence of effectiveness and develops recommendations for clinical preventive services.”

Here’s what they said:

The USPSTF recommends against routine screening mammography in women aged 40 to 49 years. The decision to start regular, biennial screening mammography before the age of 50 years should be an individual one and take patient context into account, including the patient’s values regarding specific benefits and harms.

Right below that recommendation appears this quotation from Diana Petitti, Vice Chair, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, in a highlighted box:

“So, what does this mean if you are a woman in your 40s? You should talk to your doctor and make an informed decision about whether a mammography is right for you based on your family history, general health, and personal values.”

Mammograms weren’t outlawed. They weren’t taken away. No one’s insurance stopped covering them. This was a reasoned statement that because the evidence suggests that universal screening of women in their 40s may not be doing more benefit than harm, each woman should make an individual decision with their physician. It was based on a transparent analysis that anyone could repeat. Read the full report.

But – to be honest – I don’t want to have a discussion about mammograms. It’s not my area of expertise, nor an area in which I feel especially qualified to tell you what to do. I suppose that makes me rare. But I am reasonably knowledgeable about decision analysis and how these studies are done.

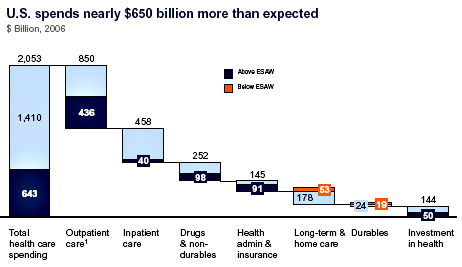

Although many seem to hate comparative effectiveness research, or cost-effectiveness research, or whatever you want to call it, those same people often seem obsessed with the cost of reform. Yet the cost of reform (maybe $90 billion a year) is NOTHING compared to the cost of health care itself ($2.5 trillion, or $2500 billion a year). The first question I am always asked is, “Why does care cost so much in the United States?” The simple answer is because everything costs too much. Look at this graphic from a McKinsey Global Institute study of healthcare:

Yes, it’s a bit overwhelming, but here’s the critical part. The dark blue bars are the amount that the US spends which is more than you’d expect for what we get in return. We like to demonize the private insurance industry, and the “wasteful” spending there is more than 60% of all spending on health administration and insurance, but it’s only a tiny percentage of overall spending. Same goes for drugs, where “wasteful” spending is less than $100 billion.

“Wasteful” spending in outpatient care, however, is over $430 billion a year. Know what that includes? Doctors. Hospitals. Nurses. Actual things patients want, like office visits and tests (even mammograms). There’s actually two and a half times more “wasteful” spending in actual care than in drugs and health insurance combined. But it’s very hard, and politically unpopular, for us to attack those providing care. So we focus on other things, facets of the system that contribute much less to the overall cost.

But if we aren’t willing to tackle wasted care, we will never truly contain costs.

How can we decide what works and what doesn’t? How can we decide what can be cut? That’s why we need comparative effectiveness research. That’s why we need bodies like the USPSTF. Independent organizations made up of people who understand the research and can inform us how some things compare to others. They’re not perfect, but they are transparent, accountable, and public.

We so often act as if everything in medicine is an unequivocal benefit. That’s simply not the case. Everything has harms as well. Ideally, the benefits outweigh the harms. Sometimes, however, that’s not the case. And sometimes, in the real world, cost is a harm.

There simply isn’t an unlimited amount of money in the budget. Each dollar we spend on stuff that doesn’t work is a dollar we can’t spend on stuff that does. Legitimate care is denied every day. Ideally, it should be denied when it doesn’t work, or isn’t providing bang for the buck.

How are we to prioritize what to pay for? That’s an excellent question. I don’t necessarily have the answer. But we need to find an answer. Putting our heads in the sand and pretending that we will never need to make these decisions will result in economic ruin. Saying that we need to cut costs and then declaring that any attempt to find places we can cut costs is rationing – sometimes even saying those two statements almost simultaneously – is not only hypocritical, it’s also dangerous.

And that’s why this last week has been so disappointing to me. Research isn’t perfect, not even that done by the USPSTF. But instead of having a debate about the merits of the findings of the USPSTF, we were flooded with politics. On day one, we were all confronted with this:

“Tens of thousands of lives are being saved by mammography screening, and these idiots want to do away with it,” said Daniel B. Kopans, a radiology professor at Harvard Medical School. “It’s crazy — unethical, really.”

This kind of rhetoric, calling the USPSTF “crazy” and “unethical” does nothing to move the debate. The “numbers of lives saved” are also not based on research.

Understand – most of the “waste” in health care comes from just this sort of stuff. It’s not easy to identify, and even harder to cut. It won’t be universally popular, and it won’t win anyone political acclaim. But it needs to be discussed and debated. Someone is always going to be upset at cuts in spending. They can’t come from nothing.

If we’re not willing even to entertain a discussion of cuts, though, we’re doomed. If we declare any recommendation to reduce expenditures as “rationing” or “unethical”, then we will go bankrupt. We need leaders willing to host a rational discussion on health care costs free from partisan rhetoric, or we might as well close up shop now.