A colleague alerted me to a study just published in the BMJ that examined how pay for performance measures worked in the UK. Let’s go to the tape:

We studied a large scale pay for performance policy in the four countries of the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland), which targeted several chronic diseases in primary care, and evaluated its impact on the management and outcomes of hypertension. Based on the proportion of patients achieving certain quality indicators, general practitioners could receive payments as high as 25% of their total income. The programme started in April 2004 and included 136 quality indicators, including five for hypertension (see web extra), one of which was the proportion of patients with blood pressures controlled to 150/90 mm Hg or less.

This natural experiment was ideal for detecting the effects of pay for performance on the care and outcomes of hypertension. Although the programme was voluntary, 99.6% of general practitioners participated. The financial incentives for doctors to achieve the quality standards were substantial; the UK National Health Service committed £1.8bn (€2.1bn; $2.8bn) in funding. Almost simultaneously (June 2004) the National Institute for Health and Clinical excellence (NICE) released guidelines for the detection and management of hypertension, which were consistent with the pay for performance intervention guidance and may have also reinforced the intervention. Using data obtained from representative primary care practices in the United Kingdom, we evaluated whether the introduction of pay for performance had an impact on quality of care for hypertension and the risk of major adverse clinical outcomes.

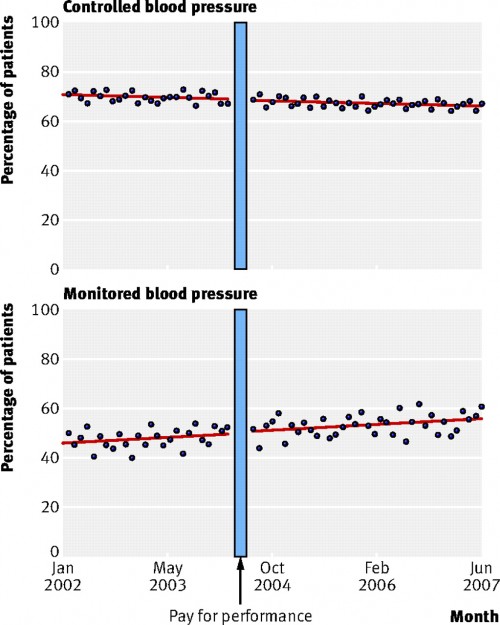

Here’s the gist. If you believe that pay for performance works, then you would expect that once the bonuses kicked in, physicians would try to earn them. In this case, you would expect to see the percentage of patients with their high blood pressure controlled go up. From 2000 to 2007, there were over 470,000 patients with hypertension (high blood pressure) that were examined for this study. The pay for performance incentives kicked in mid-2004. Let’s see what happened:

The top chart shows the percentage of patients whose blood pressure was controlled. As you can see, things were improving slightly before the pay for performance kicked in. After it did, there was no change in the trend. The economic incentive program had no effect. The bottom chart shows the percentage of patients who were having their high blood pressure monitored. No change there because of the program either.

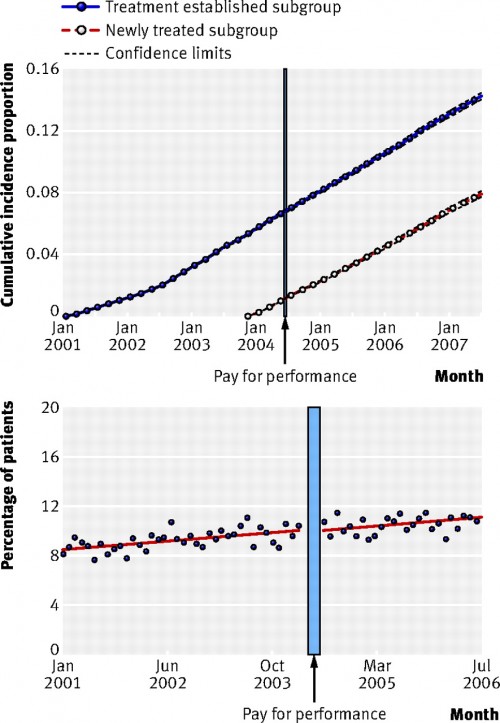

I concede that these are process measures. But process measures are often how pay for performance is operationalized. We measure whether labs are drawn or visits happen, not how sick patients get. But let’s say we did. Was there a difference in outcomes?

No. The top chart here is the cumulative percentage patients in the study who had a heart attack, heart failure, stroke, or renal failure. There was no difference in the cumulative rate before or after pay for performance kicked in. The bottom chart is the percentage of patients who died. No effect there either.

Pay for performance didn’t work. Now I know many of you are going to argue that the UK is not the US. I concede the point. But there’s no reason to believe that the docs there wouldn’t be interested in economic incentives. And the incentives are large here. Physicians could receive bonuses up to 25% of income? That’s an enormous amount of money. Heck, I think even I would be enticed by that amount.

So why did this fail? Perhaps the doctors were already improving without the program. If that’s the case, though, then you don’t need economic incentives. It’s possible the incentives were too low. But I don’t think many will propose more than a 25% bonus. It’s also possible that the benchmarks which define success were too low and therefore didn’t improve outcomes. There’s no scientific reason to think that the recommendations weren’t appropriate, however.

More likely, it’s what I’ve said before. Changing physician behavior is hard. It’s the reason I think tort reform won’t be a huge cost-saver either. But this is bad, because many people have hung their hat on pay for performance being the solution to health care quality and costs in the US. This study adds to the body of evidence that says that’s not the case.

The same colleague who told me about the study suggested that we need to change the organizational structure of the practice, ie change the system, so quality doesn’t rely on one person or one process. I agree that’s much more likely to work. Others will say that’s the point of ACOs. But as we’ve discussed before, there are lots of reasons to believe ACOs won’t lower costs (or improve quality). Moreover systems level changes would be harder, perhaps require investments up front, and not make for good sound bites. It might be better policy, but it doesn’t make for better politics.

So for now, we’ll likely continue down this potential dead end.