Kevin Outterson is an associate professor of law at Boston University. This is second in a series on legal issues with ACOs.

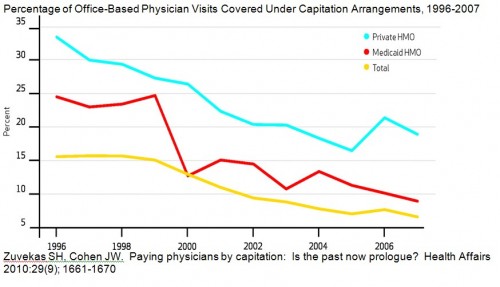

Shared payment models are a key component of ACOs. But since the mid-1990s, capitation has been is a clear downward trend as a payment mechanism in the US. As Ezra might say: “Why ACOs won’t be easy, in one graph”:

ACOs will be both clinically and financially responsible for some segment of patient care. When PPMs tried this in the 1990s, some states demanded that the physician groups obtain an insurance license, especially if they were financially responsible for care they couldn’t provide directly (like inpatient hospital care).

The West Coast was (and is) the leader in capitation. After an extended legal dance, California granted a license to MedPartners in March 1996, allowing their physician groups to accept insurance risk through partial and global capitation. Insurance regulators look for solvency, not clinical excellence. In the case of MedPartners, they got neither. When MedPartners’ California operations ran huge deficits, the state closed them down. Thousands of doctors were left hanging without a payment stream and many more patients were disrupted both financially and clinically.

The federal government also got into the PPM insurance regulation game. In the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Congress delegated “negotiated rulemaking” authority to HHS to create a federal insurance license for provider-sponsored organizations to accept risk under Medicare Part C. At the time, physician groups considered this a “golden opportunity.” I attended these negotiations on behalf of PPMs seeking a license. The interim final rules were published in April 1998, just as the PPM markets were beginning to unravel.

One lesson learned was that PPMs did a poor job managing medical and financial risk. PPMs failed despite significant physician participation (many PPMs were led by physicians; many physicians were employed; others were tied in long-term contractual arrangements; most had equity stakes). Either the physicians were unwilling or unable to manage care for financial targets, despite significant amounts of their money at risk.

The second take away: insurance regulation worked. Not only did it inject some financial discipline into the sector, but problems were identified and dealt with in relatively good order. Most importantly, the capital requirements of the state and federal rules undoubtedly deterred many more from jumping into the game in 1996-1999. Say a word of thanks to the NAIC.

So, for ACOs – how exactly will physicians manage financial risk care better this time? And let’s be appropriately skeptical of claims that ACOs need exceptions to normal insurance solvency rules.