Co-blogger Steve and I, as well as some of our colleagues, were hoping that health reform would finally bring competitive pricing (or bidding) to Medicare Advantage (MA). It won’t, though it nearly did. That’s very disappointing and possibly not a good thing for beneficiaries, the program, or taxpayers.

Competitive pricing seemed a lock when the Senate bill appeared to be the only one that could pass both houses. Unlike the House bill, it called for MA plans to compete on price. Of course today it is the law of the land. But the budget reconciliation amendments will undo competitive bidding and replace it with a modified version of the existing administrative pricing system (which sets MA payments by fiat) <sigh>.

The new MA payment system is hard to understand from the legislative text. The various summaries on Nancy Pelosi’s website explain it succinctly, though leave out a few important details. Colleague Roger Feldman went to the trouble of producing a summary superior to these other source, which is the basis for the following.

In 2011 government payments to MA plans will be fixed at 2010 levels. In 2012 payments will be a 50/50 blend of the current levels and a “benchmark” obtained via a new formula. In subsequent years payments will also be a of blend current and new levels but one that gradually includes more of the latter so that by 2018 all plans are paid according to a new benchmark formula. That formula will be the product of local per beneficiary costs (those of fee for service (FFS) Medicare) and a percentage that varies by quartile of local costs:

- For areas in the highest quartile of all areas for the previous year the percentage is 95%;

- For areas in the 2nd highest quartile, 100%;

- For areas in the 3rd highest quartile , 107.5%;

- For areas in the lowest quartile, 115%.

Payments are also capped so that they are no higher than what they would be under the current system. Bonus payments would be offered for efficiency and quality. As convoluted as that may seem, it is (almost) simpler than the current payment system (except for the fact that the current system is actually embedded in the new one as a cap–ugh!).

Some immediate questions come to mind:

- Why are payments a higher percentage of costs where costs are low and a lower percentage of costs where they are high?

- What motivated the switch from the Senate’s planed competitive bidding to a continuation of administrative pricing?

- Why aren’t rates capped at 100% of FFS costs as advocated by MedPAC and written into the House bill?

- How will the new payments affect taxpayer costs and MA plans’ availability, benefits, and enrollment?

I can answer questions 1-3 and likely will in another post (unless co-blogger Steve gets to them first). Question 4 was studied by CBO, which scored the savings at $131.9 billion over 2010-2019. Their analysis showed that MA enrollment would be lower by 4.8 million relative to a projection of current law in 2019. On average they expect the value of benefits to decline by $67 per member per month in 2019. See the CBO document for additional analysis. So, taxpayers win and some beneficiaries lose, though it depends on county cost type (high vs. low). (A prior post explained that even though beneficiaries lose something with MA cuts, the economic value of that loss is very low.)

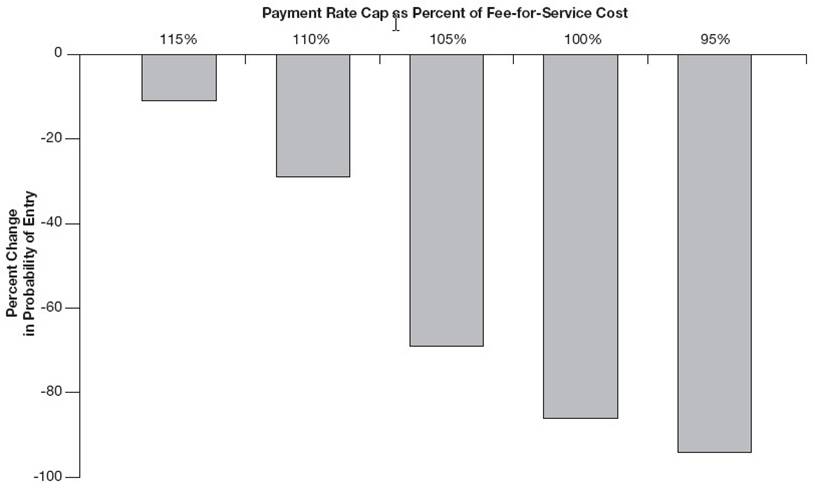

At the moment I can only add one thing to these findings. In a paper summarized on this blog Steve Pizer, Roger Feldman, and I published a graph (reproduced below) that illustrates the effects of different payment rates (relative to FFS costs) on market exit of private fee for service (PFFS) plans. PFFS is the highest cost MA plan type and is different from the MA HMO type in important ways that make it unreasonable to extrapolate PFFS findings to the entire program. So take all of the following with a sack of salt.

The figure shows the change in probability of a PFFS plan market entry for various levels of payment to FFS cost ratio (click to enlarge). The results are qualitatively illustrative of the relative degree of market exit by payment rate for MA plans but should not be interpreted to apply quantitatively to the non-PFFS part of the MA program. A payment of 115% of FFS cost results in about a 10% reduction in PFFS entry, while a payment of 95% of FFS cost would all but eliminate the PFFS plan type.

Change in PFFS Market Entry by Payment/FFS Cost Ratio

Based on these results, I would expect relatively small reductions in MA plan availability in high payment-to-cost areas (payment 115% of FFS cost). Areas with the lowest payment-to-cost ratio (95% of FFS cost) may see considerable reductions in MA offers. However, 95% of FFS cost was the prevailing rate prior to 1997 and plans did serve high cost areas then. So it is likely that some plans may remain in markets even if they’re paid 95% of costs. Also, efficiency and quality bonuses would increase payments for plans that qualify for them. To what extent markets that currently have plans will be left without any is not something about which I care to even hazard a guess.

So, this new administrative payment rate scheme could be pretty disruptive to the MA market and the beneficiaries it serves. I think a competitive bidding system would be less so. I’m also concerned that the new system won’t stick, that Congress will find an excuse to undo it, increase payments, and then, poof, there go the MA savings. Competitive bidding would be less prone to such political monkeying, though not immune. Such a competitive system is working very well in the Medicare Part D (drug benefit) market. Why not try it in the MA program? I could answer that but this post is long enough.