Health reform, even with a public option, will be built largely on a private insurer infrastructure. That means hundreds of billions of dollars will be pumped through insurance companies on their way to payment to providers for health care services. Given this reality, we should all want as efficient a health insurance market as possible.

This appears to be the beginning of an argument for encouraging additional competition among health insurers. Greater competition is the source of greater market efficiency, isn’t it? The answer is, it depends on the market. The simple type of idealized market taught in Econ 101 does become more efficient (in an economic welfare sense) as competition increases. But other types of markets–in particular, so called two-sided markets, among others–do not always behave this way. And health care is one of them.

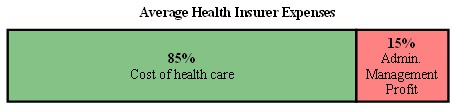

Let’s first consider the best-case scenario for the consequences of greater competition in the health insurance market. About 85% of insurers’ costs are medical. The remaining 15% is for administration, marketing, management, and profit (profit itself is about 6% at the time of this writing). With additional competitive pressure insurers would compete away some of that 15%. Perfect competition would reduce profit to zero and may force efficiencies elsewhere. So, perhaps the best competition could do would be to cut in half that 15% for administration, marketing, management, and profit.

Now a 7.5% reduction is not chump change. It represents a lot of money, tens of billions of dollars annually. But that’s only an optimistic best case. And it pales in comparison to the cost savings that are available on the provider side, the 85% of insurers’ costs. (Hat tip: Michael Chernew.)

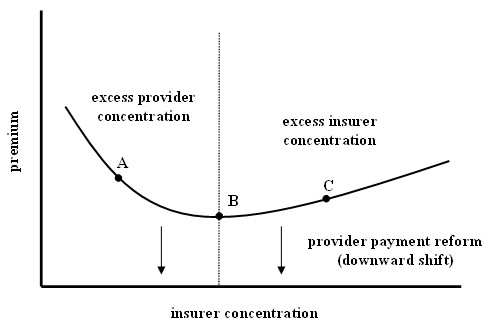

If we really wish to understand what would happen if the insurance market is made more competitive we have to go one step further. There is a reason the health care market is not analyzed in Econ 101. It is much more complex than, say, the market for coffee. In fact, additional competition in the health insurance market could drive costs up. Here’s a a graphical depiction of what I have in mind.

Figure 2

The figure is drawn for a fixed level of provider market concentration. The horizontal axis is insurer market concentration, and the vertical axis is premium for a standardized plan. Relative to the fixed level of provider concentration, insurer concentration is high in the region of point “C,” and premiums are above the minimum possible level. Insurers are charging above the competitive premium level because they have excessive market power. In this region, higher premiums stem from higher insurer profits and/or lack of administrative efficiency (the red zone of Figure 1).

The figure is drawn for a fixed level of provider market concentration. The horizontal axis is insurer market concentration, and the vertical axis is premium for a standardized plan. Relative to the fixed level of provider concentration, insurer concentration is high in the region of point “C,” and premiums are above the minimum possible level. Insurers are charging above the competitive premium level because they have excessive market power. In this region, higher premiums stem from higher insurer profits and/or lack of administrative efficiency (the red zone of Figure 1).

On the other hand, insurer concentration is low relative to that of providers in the region of point “A,” and premiums are again above the minimum because insurers can’t negotiate down to the lowest possible price with providers. Providers have too much power relative to insurers and are charging prices above the competitive minimum. Insurers pass those high prices onto consumers through higher premiums. In this case, higher premiums stem from higher medical costs (the green zone of Figure 1).

As provider power weakens the whole curve shifts downward, and as provider concentration increases the whole curve shifts upward.

If we’re now at point “C” (and this is by no means certain) it may be possible to achieve lower premiums by diluting the insurance market, weakening insurers with respect to providers. But if we go too far, we’ll shoot past the optimum “B” and be no better off. On the other hand, if we’re now at point “B” we should do nothing to upset the insurer-provider balance of power. And if we’re at point “A” then it is the provider market, not the insurance market, that has excess concentration.

As far as I know, nobody knows which of the many local health care markets are operating at “A”, “B”, or “C.” In fact, I have not yet seen any studies that can tell us what mix of insurer-provider market structure achieves the optimal point “B.”

It is worth noting that what is being considered in Washington as the long-term solution to health care costs has less to do with finding an optimal mix of insurer-provider power and more to do a change in the incentives of provider payment. The goal is to shift the entire curve in the figure above downward so that in every type of market–“A,” “B,” and “C”–health care costs and premiums come down. But a downward shift due to payment reform may be offset by a movement leftward along the curve. Such an offsetting effect could be brought about by antitrust action against insurers, weakening their market power with respect to providers. A similar offset could occur through additional integration of providers under a payment reform model (ACOs, CHTs). Both of these potential offsets are included in current legislation.

There is more to say about health care costs from a market theory point of view. I will be returning to this issue and referring to Figure 2 in the near future. The bottom line, however, is that the failure of policymakers to consider the insurer-provider balance of power may prove to be a costly oversight.