We’ve said it before, many times and in many ways: workplace wellness programs don’t save money.

Last week, on the Health Affairs blog, Al Lewis, Vik Khanna, and Shana Montrose said so too, adding some nuance we have not included in our posts on TIE. You should read the whole thing. Here are a few of my favorite passages:

It is beyond the scope of this posting to question non-peer-reviewed vendor savings claims that do not use any recognized study design.

I just love this phrasing of “we’re not reviewing crap.” Next, here’s a difference-in-differences blooper (or, really, a failure to do a real diff-in-diff analysis):

As an example of overstated savings, consider one study conducted by the Health Fitness Corporation (HFC) about the impact of the wellness program it ran for Eastman Chemical’s more than 8,000 eligible employees. […]

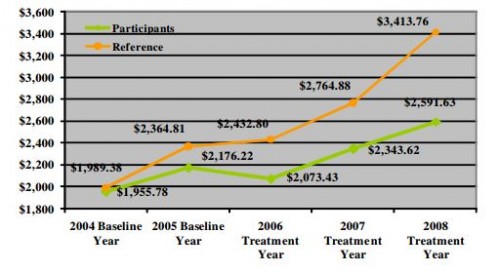

[F]igure 1 below shows that despite the fact that no wellness program was offered until 2006, after separation of the population into participants and non-participants in 2004, would-be participants spent 8 percent less on medical care in 2005 than would-be non-participants, even before the program started in 2006. In subsequent presentations about the program, HFC included the 8 percent 2005 savings as part of 24 percent cumulative savings attributed to the program through 2008, even though the program did not yet exist.

Finally, for workplace wellness programs to save money, they have to save more than the cost of implementing such programs. Lewis, Khanna, and Montrose say exactly why this is hard:

Data compiled by the Health care Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) shows that only 8 percent of hospitalizations are primary-coded for the wellness-sensitive medical event diagnoses used in the BJC study. To determine whether it is possible to save money, an employer would have to tally its spending on wellness-sensitive events just like HCUP and BJC did. That represents the theoretical savings when multiplied by cost per admissions. The analysis would compare that figure to the incentive cost (now averaging $594) and the cost of the wellness program, screenings, doctor visits, follow-ups recommended by the doctor, benefits consultant fees, and program management time. For example, if spending per covered person were $6,000 and hospitalizations were half of a company’s cost ($3,000), potential savings per person from eliminating 8 percent of hospitalizations would be $240, not enough to cover a typical incentive payment even if every relevant hospitalization were eliminated.

Now maybe Lewis et al. and TIE bloggers are wrong about wellness programs. Maybe they can save money. That’d be fine, if true. What we want, though, is evidence, not claims from industry studies based on study designs that cannot produce valid causal estimates without heroic assumptions. Show us the credible evidence and we’ll sing a different tune. Until then, so far, wellness programs look like a cost loser.