This blog has a long and detailed record on concern over health care spending. My posts have also acknowledged how difficult I think it will be to bring that spending under control in the future. After all, every bit of spending goes into someone’s pockets, and taking it away will be a massive hit in the wallet for many, many Americans.

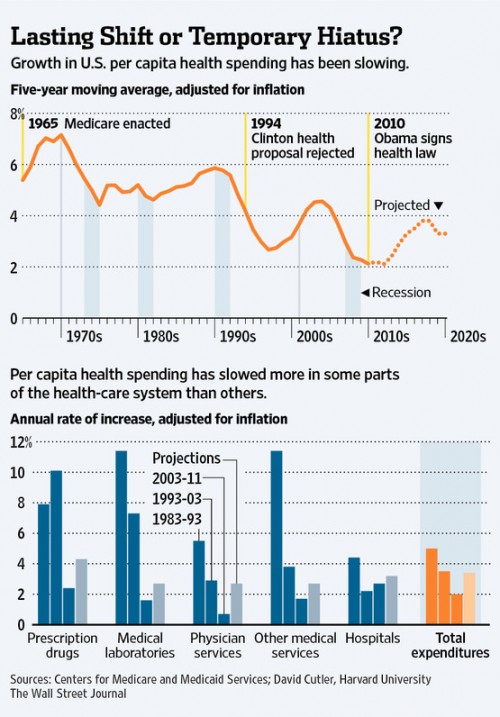

There’s a piece in the WSJ yesterday, though, that questions whether things are actually getting better organically:

For the past couple of years, U.S. health-care spending has been growing at a surprisingly slow pace.

A lot of this is the recession and its aftermath. Americans cut back spending on nearly everything but iPhones. They go less frequently to the doctor, put off elective procedures and cut back on prescription drugs. It is the most significant slowdown in health spending since the heyday of managed care in the late 1990s.

“This has gone on longer than anyone expected, though the [economic] downturn has too,” says Larry Levitt of the Kaiser Family Foundation, which tracks health-spending trends.

Now this slowdown in utilization may not be a universal good. There’s lots of evidence that Americans aren’t necessarily great at distinguishing between necessary and unnecessary care when it comes to saving money. But this appears real, nonetheless:

Some are arguing that this has to be temporary, because there have been no major shifts in national policy, nor any concerted efforts to change the health care system on a national level (such as the managed care experiment of the ’90s). Others disagree, though:

Harvard University economist David Cutler draws the opposite conclusion. He attributes about a third of the slowdown to the transitory impact of the recession, and another dollop to recent cuts in government payment rates to providers and to the drug industry’s inability to find pricey new drugs to replace the revenue from generics.

But Mr. Cutler speculates a significant part of the slowdown reflects changes in consumer and provider behavior that will persist. Americans are using less health care because they are being forced to pay more out of pocket. Indeed, the share of insured workers with deductibles of $1,000 or more rose to 31% in 2011 from 18% in 2008, Kaiser estimates. “A lot of people are saying: Do I really need this?” Mr. Cutler says, who notes a distinct slowing in the pace of spending on CT scans, MRIs and other imaging.

At the same time, he says, doctors and hospitals—prodded by employers and government—are changing the way they deliver health care, partly in anticipation of some features of the Obama law, such as penalties for hospital-caused infections.

No one knows for sure, of course. If you forced me to answer, I’d say that I agree that our spending has been affected by a lack of new pricey pharmaceuticals as well as by increased cost-sharing. But both of those developments have their down sides. I’m less convinced that it’s early implementation of the ACA. I’d be happy to be proven wrong.

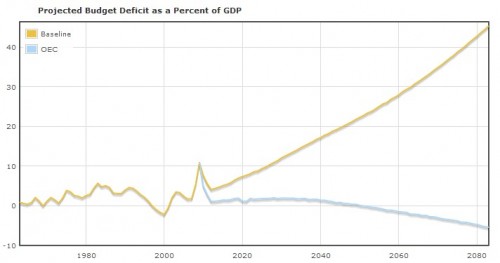

Let none of my concerns, however, diminish the real potential for improvements in our long term fiscal health if this trend holds. As a reminder, here is a chart from the Health Care Budget Deficit Calculator, produced by the Center for Economic and Policy Research:

The yellow line is our projected deficit as a percent of GDP if things go along unchanged. The blue line is our deficit (surplus) if our health care spending instead increased at the rate of the average of the OECD countries. That’s the only change there. Keep on spending on defense, keep our planned discretionary spending, keep the Bush tax cuts. Let’s say it again – we don’t have a deficit problem, we have a health care spending problem.

If we could get a little bit better at this, or if these trends continue or imporve, our long term fiscal outlook looks a heck of a lot better.