In 2013, the Swiss Medical Board was asked to review the use of screening mammography. Two of the participants have penned a piece in the NEJM that’s just amazing. Here’s a bit (emphasis mine):

First, we noticed that the ongoing debate was based on a series of reanalyses of the same, predominantly outdated trials. The first trial started more than 50 years ago in New York City and the last trial in 1991 in the United Kingdom. None of these trials were initiated in the era of modern breast-cancer treatment, which has dramatically improved the prognosis of women with breast cancer. Could the modest benefit of mammography screening in terms of breast-cancer mortality that was shown in trials initiated between 1963 and 1991 still be detected in a trial conducted today?

Second, we were struck by how nonobvious it was that the benefits of mammography screening outweighed the harms. The relative risk reduction of approximately 20% in breast-cancer mortality associated with mammography that is currently described by most expert panels came at the price of a considerable diagnostic cascade, with repeat mammography, subsequent biopsies, and overdiagnosis of breast cancers — cancers that would never have become clinically apparent. The recently published extended follow-up of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study is likely to provide reliable estimates of the extent of overdiagnosis. After 25 years of follow-up, it found that 106 of 484 screen-detected cancers (21.9%) were overdiagnosed. This means that 106 of the 44,925 healthy women in the screening group were diagnosed with and treated for breast cancer unnecessarily, which resulted in needless surgical interventions, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or some combination of these therapies. In addition, a Cochrane review of 10 trials involving more than 600,000 women showed there was no evidence suggesting an effect of mammography screening on overall mortality. In the best case, the small reduction in breast-cancer deaths was attenuated by deaths from other causes. In the worst case, the reduction was canceled out by deaths caused by coexisting conditions or by the harms of screening and associated overtreatment. Did the available evidence, taken together, indicate that mammography screening indeed benefits women?

There’s only so many times you can say the same thing. It does not appear that universal screening reduces mortality. But what’s even more stunning is how much women misunderstand this fact:

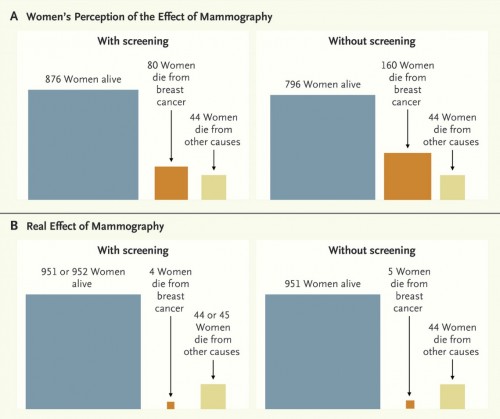

The bottom half of this pic shows the actual effect of mammography. If we take 1000 women age 50 and watch them for 10 years, and don’t screen them, 5 will die of breast cancer, 44 will die of other causes, and 951 will be fine. If we do screen them, then 4 women die of breast cancer, 44 or 45 die of other causes, and 951 or 952 are fine. This is why the effects seem to be negligible.

But if you ask women to estimate how well mammography works, then you’re in for a whole different ballgame. They think that without screening, of those 1000 women, 160 are going to die from breast cancer in the next 10 years. They way, way, way overestimate the danger. They also overestimate the effectiveness of mammography. They think that it will halve the rate of death, so that only 80 of the 1000 women will die from breast cancer.

Therein lies the problem. If you think that breast cancer is going to kill 16% of all 50-year-old women in the next 10 years and that mammography makes a huge difference in the mortality rate, then you’re going to demand a universal screening program. Hell, I’d demand it if that were the case. Until we can change the perception of the public to more closely match reality, and make them realize that the harms may outweigh the benefits, we’re going to get nowhere in trying to make changes.