In our Hamilton Project paper, Nicholas, Amitabh, and I propose a reference pricing scheme as one part of a package of ideas to manage the rate and composition of innovation of health care technology. If you’re already thinking about CalPERS’ reference pricing approach—about which I’ve written a lot (here’s one post)—you’re on the wrong track. Though we’ve never seen the distinction clearly drawn in the literature, there are two notions of reference pricing out there, and we mean the other one.

That other one has been used for prescription drugs in Canada (British Columbia), Germany, Norway, Spain, and other countries, as well as two employers (in the US and Canada)—see the systematic review of reference pricing by Lee et al. It also arises in the clever proposal by Pearson and Bach.

The basic idea is to group therapies (like drugs, but also procedures or technologies) according to their therapeutic effect. Then, one sets a one price—the reference price—for each group in some way. It could be the price associated with the most cost-effective treatment, for instance. Notice, however, that that price could vary across providers, maybe paying a higher quality provider more, another less.

I call this vertical reference pricing. It’s set within provider, but applies across technologies grouped by therapeutic effect. That’s very different from what I call the horizontal reference pricing of CalPERS, which sets one price for, say, a knee replacement and applies that across all providers.

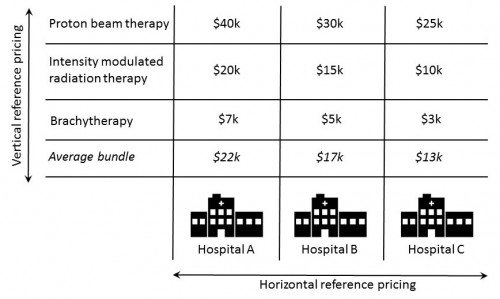

Let’s play out the differences between vertical and horizontal reference pricing for the three prostate cancer treatments offered at three different hospitals and at prices shown in the chart below. (Yes, there are other prostate cancer treatments, like prostatectomy and watchful waiting, but for simplicity let’s pretend for the moment that these are the only three we know of.)

Horizontal (CalPERS style) reference pricing would pick one price for prostate cancer treatment, perhaps something like the “average bundle” price of $13k at hospital C, which hospital C has agreed to accept for payment in full for any prostate cancer treatment (no out-of-pocket cost for the patient). It would then offer that price to any hospital. If a patient received prostate cancer treatment at hospital A or B, he might pay more out of pocket for it because some therapies offered at those hospitals cost more than $13k.

This puts considerable pressure on the patient to shop for a hospital that will accept the reference price as payment in full or for the patient to weigh the quality-price trade-off at hospitals that won’t. It puts considerable pressure on the insurer to set a price low enough to reap savings but high enough such that there are sufficient high-quality and affordable choices in the market, something not all markets can support. Adhering to a reasonable access standard would also impose an ongoing, management overhead cost. These are among the critiques one can level at horizontal reference pricing (see Frankford and Rosenbaum).

Many of those critiques do not apply to vertical reference pricing, however. Let’s play out the prostate cancer example to see why. For example, imagine pegging the hospital-specific vertical reference price to the most cost-effective prostate cancer treatment (among the three in the chart). Let’s say that’s intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT).* Vertical reference pricing would pay the hospital-specific IMRT price ($20k, $15k, $10k at hospitals A, B, C, respectively). If a patient wanted proton beam therapy at any of these hospitals, he’d pay the (hospital-specific) difference.

The advantage of this kind of vertical reference pricing is that it guides the patient toward more cost-effective technologies, and fully covers it or anything cheaper at any provider (or any provider in the insurer’s standard network). One need not shop around if one is OK with cost-effectiveness. It also guides manufacturers toward development of cost-effective technologies.

There are, of course, many variants, like pegging the vertical reference price to the most demonstrably effective therapy (ignoring cost). This at least spares the insurer the cost of more expensive and unproven therapies, but partially compensates any patient that wants it. Our proposal is closer to this approach, but we bring in the idea that no price (per QALY) should be greater than a cost-effectiveness threshold.

We also propose that Medicare pay whatever it otherwise would for cost-effective therapies priced below the reference price. An implication of this approach is that something as cheap to Medicare as, say, brachytherapy for prostate cancer remains just that cheap. It is not paid for at the reference price. Under horizontal reference pricing, on the other hand, it would get reimbursed at the same reference price as any other prostate cancer treatment, which would overcompensate providers for it.

I refer you to our paper for the details on reference pricing and our other proposals, which complement it. You can also attend the event at Brookings tomorrow at which it will be discussed.

* I don’t know if that is, in fact, the most cost-effective therapy. Let’s just pretend it is for this example.