“Simply put” is an ongoing series. See the introduction for an explanation of the series and the full list of topics that have been or may be covered. Feel free to suggest other topics in that post.

A doctor and an economist have the following conversation:

Doctor: There is no waste in health care. Allof care I provide my patients is valuable. Every bit improves health.

Economist: That last little bit of care you provide costs far more than it is worth. It’s a waste of resources. You’re reducing, not increasing, welfare.

Doctor: Reducing welfare? Ridiculous! My job is to benefit patients and the public. That’s what I do.

Economist: Benefiting patients and the public? Don’t be so sure! My job is to point out where we can make better use resources. That’s what I do.

What’s this argument about? And who is right? It’s about two different views of “welfare” and both the doctor and the economist are right (or could be). It all can be explained in terms of marginal benefit and marginal cost.

Let’s start with one thing the doctor and the economist can both agree on. It’s the following intuitive idea: any good or service a person buys is worth at least as much to that person as the money that person spent on it. From this idea it follows that people will buy more of something the less they have to pay for it.

The maximum amount of money someone will spend on a good or service is called that individual’s valuation of that good or service. We can think of it as a monetized form of the benefit (or utility, in economist speak) they’ll derive from that good or service. If you’d spend up to $3 for a cup of coffee at a coffee shop but not a penny more, then $3 is your valuation of that cup of coffee. Though you may be willing to spend $3 for the first cup, you may not be for a second, or third, or tenth. If the price is lower, say $1 per cup, you might be more willing to buy more than one cup, however.

You’ll keep buying cups of coffee until the increase in benefit you’d get from the next cup is lower than the additional amount you’d have to spend on it. Notice those words “increase” and “additional”? Those are synonyms for another term economists use, marginal. So long as the marginal benefit exceeds the price, you’ll keep buying. This just means you keep buying something (coffee, whatever) until you no longer think it is worth it, given how much you’ve already bought (or consumed). This should be intuitive. It’s how you decide how many cups of coffee to buy at the coffee shop, or how many bananas to buy at the super market, or how much of anything to buy.

It’s true for health care too. Now, purchasing health care is more complicated because of insurance. But the same idea applies. You’ll consume as much health care as you think worth it for the transaction price (your copayment if you’re insured). The lower the price, the more you’ll consume. You’ll keep using health services until the marginal benefit falls below the price you pay.

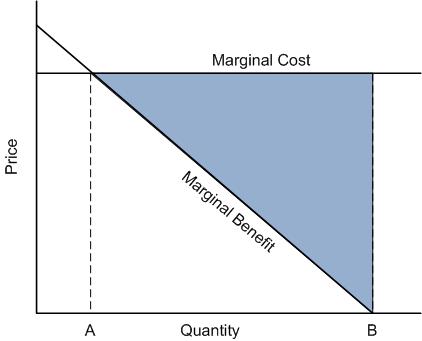

Imagine you’re fully insured. (You pay no copayment.) You pay nothing for each health care service. How much will you use? Well, if it costs you $0 for a service you’ll use as much of that service until the marginal benefit is $0. So long as the service is at least providing a tiny bit of benefit (to your health, or just because you enjoy the experience for some reason), you’ll keep using it. This is illustrated in the following diagram. The vertical axis is price (that you pay out of pocket) and the horizontal axis is the quantity you’ll use. The downward sloping line is marginal benefit. It slopes downward for the reasons given above; lower price means you’ll buy more. You’ll use quantity B because that’s the quantity for which marginal benefit reaches the price you pay, $0 (because you’re fully insured).

So long as you’re benefiting from the service, the physician is likely willing to provide it, particularly if he perceives the benefit is at least not harming your health. In other words, the physician is inclined to provide quantity B of health services too. To the physician and the patient, all of that health care is “welfare” improving in the sense that it improves your health, or doesn’t harm it, anyway. (Qualitatively, the story doesn’t change if the patient is not fully insured, but pays a copayment. In that case, the horizontal axis in the figure is not at the $0 price level, but at the copayment level.)

The economist considers not just marginal benefit, but the (full) marginal cost. Imagine each health service costs a fixed amount, as shown by the marginal cost line in the figure. For example, each service costs $100, no matter how many are provided. (The story is not much different if marginal costs varies.) The insurance company may be paying most or all of that $100, but it is still a cost. It reflects real resources used (physician time, supplies, etc.).

The economist notices that the marginal benefit falls below marginal cost at quantity A. All the resources used to provide B-A services cost more than they’re valued by the patient. This is termed a “welfare loss” by economists because it reflects a misuse of resources in the following sense. If the patient were handed enough cash to buy B health care services, she would not buy that many. She’d buy the amount A and use the rest of the money for something else (like coffee). The cost reflected by the blue triangle in the figure is, in this sense, “wasted.” The patient only receives a benefit reflected by the marginal benefit line and all the cost of providing care that is above that line and to the right of A (the blue triangle) is economic waste, even if it is health improving.

Economists term the area of the blue triangle “deadweight loss.” To them it is a welfare loss even as the doctor (and patient) may perceive it as a health (or welfare in another sense) gain.

This is the crux of the debate between the doctor and the economist. One sees point B as providing the greatest value, the other point A. Who is right? They both are. “Waste” and “welfare” mean different things to each of them. To the right of A, marginal benefit is below marginal cost, notwithstanding any health improvements. The doctor sees providing quantity B as his job, the economist sees limiting provision to quantity A as his. If you already see how this relates to the notion of “rationing,” you’re on the right track.

Further Reading

Newhouse J. Pricing the Priceless: A Health Care Conundrum.