Don A in Pennsyltucky asked,

Do wellness programs work? Is i[t] acceptable for an employer to provide a discount to employees who participate?

These are good and timely questions since in 2014 the Affordable Care Act will raise the legal limit on wellness program incentives from 20% to 30% of coverage cost, but only for wellness programs that actually reduce health care spending. For tobacco-related interventions, employers can charge tobacco users up to 50% more in premiums. Note that these are only for interventions related to changing or meeting measurable health standards. For screening incentives, there is no legal limit.

For wellness programs, there are two notions of “working,” health improvement and cost saving. The evidence on both is not very encouraging. In fact, earlier this year I posted about studies that suggested they do not save money. That was far from a comprehensive review, however. So, let’s do this a bit more systematically.

First of all, if you Google “do wellness programs work,” you’ll pull up many recent posts in response to the release of a congressionally-mandated study on wellness programs by RAND. The study included “a literature review, a national survey of employers, case studies of workplace wellness programs, and statistical analyses of medical claims and program data.” Here are a few, key points from the report:

- Half of U.S. employers with 50 or more employees (encompassing 75% of the workforce) offer wellness programs.

- There are two flavors of wellness program activities: screening and interventions. Most companies offer both types.

- Interventions relating to fitness, weight, and smoking are the most common, though there are others (e.g., substance use, stress management).

- Participation is low. Less than half of employees at companies that offer wellness programs undergo screenings or risk assessments. Of those identified as eligible for an intervention, less than one-fifth participate.

- In an analysis of a database supplied by a trade organization of the health and wellness industry,* RAND found that wellness programs were associated with “statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in exercise frequency, smoking behavior, and weight control, but not cholesterol control.” Nevertheless, the observed changes were small. Their analysis does not “account for unobservable differences between program participants and nonparticipants, such as differential motivation to change behavior.” In other worse, it’s possible they’re driven by selection bias.

- These results are consistent with those of other studies that found wellness programs associated with “increased smoking cessation, […] improvements in physical activity, higher fruit and vegetable consumption, and lower fat intake as well as a reduction in body weight, cholesterol levels, and blood pressure.” However, many of those other studies are not well designed (more on that tomorrow).

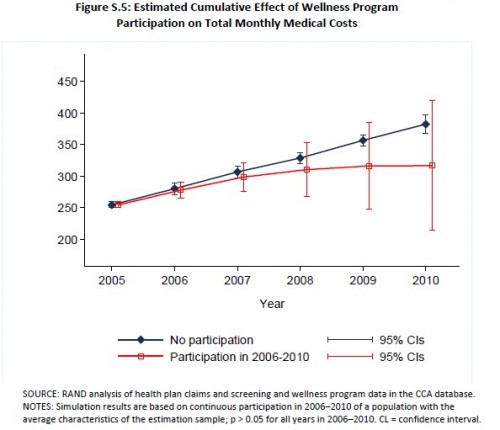

- Without much analysis, employers overwhelmingly believe wellness programs save money. RAND found they did, but not to a statistically significant degree after four years. Chart:

- “The peer-reviewed literature indicates that financial incentives may attract individuals to enroll or participate in smoking cessation programs and increase initial quit rates, but they generally do not achieve long-‐term behavior change []. Results from one randomized control trial found that large incentives (of up to $750 over the course of a year) were effective in improving abstinence rates, even when incentives were no longer offered [].”

The RAND study is far from the only one on wellness programs. I’ll comment on some others and finish addressing Don A in Pennsyltucky‘s questions in a follow-up post tomorrow.

* Just saying.