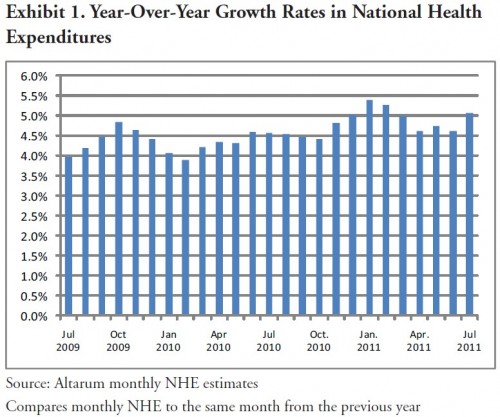

In a post earlier today, I discussed the evolution of health care spending growth. Below is one more chart from the Altarum Institue that illustrates that health spending growth has not accelerated dramatically in recent months, certainly not enough to explain this year’s jump in employer-sponsored health insurance premiums. They’ve grown about 9% this year, up from 5% or lower over the past few years. As the chart shows, national health expenditures have been consistently growing at rates below 5.5%.

Health spending is obviously relevant to premiums, but many other factors affect premium growth too. What everyone wants to know is why employer-sponsored health insurance premiums jumped up so much this year. Since health care spending growth has been low — at near 1990s levels — we can rule that out as an explanation.

Moving on, let’s consider some other things. For what follows, I’ve been aided by Charles Roehrig and colleagues of the Altarum Institute, with whom I exchanged email on this topic. The title of this post is explained in the final entry of the following list (“The underwriting cycle”).

Besides total health spending, what else affects premiums?

Profits. Insurers have been reporting a big profits lately, which implies premiums growing faster than costs.

Expectations. It’s possible insurers expected more utilization than actually occurred this year. In other words, premiums jumped due to expected spending, not actual spending. After all, premiums are established before the spending occurs. On the other hand, FEHBP premiums did not rise by nearly as much. Did insurers for that program have different expectations about spending? Hard to imagine. It’s the same insurers crunching the same data as the rest of the commercial market.

Anticipations. Maybe insurers believe that in light of health reform and increased scrutiny of premium growth, this was their last chance to increase rates to the extent they did.

Insurer Market power. Insurers may simply have had the market power to profitably raise prices to the extent they did. Maybe they have such power in the broader commercial market but not in FEHBP. (That’s plausible, given how FEHBP works.) On the other hand, self-insured firms raised premiums about the same amount. So, it is hard to fully buy a market power argument.

Cost shifting (or provider market power). Perhaps private premiums are rising because Medicare and Medicaid payments are falling, the standard cost shifting argument. This is a possible factor, though given plausible rates of cost shifting, it probably does not explain all or even most of the premium increase. Note that cost shifting is incongruous with an insurer market power argument. Also, cost shifting relies on a provider market power. That hospitals may be gaining market power is part of what makes it plausible.

Changing risk pool. The rate of uninsurance has been growing. Perhaps those who remain insured are older and relatively less healthy (adverse selection). This would explain both low health spending growth overall (the uninsured use less) and higher premiums (the relatively less healthy who remain insured use more per person). What’s crucial to recognize here is that as far as premiums are concerned, total health spending is less important than health spending by insurers per insured person. So it matters who the insured are.

Coverage mandates. The ACA requires insurers to cover preventative benefits without cost sharing and children until age 26 without underwriting. These explain 1-2 percentage points of the 8-9 percentage point increase in 2011. Based on a new Aon Hewitt report, Sarah Kliff blogged in detail about the effects of ACA coverage mandates on recent premium increases.

Consumer-directed health care. More employees are enrolled in high deductible health plans than ever before and those deductibles are increasing. The trade-off for higher deductibles is supposed to be lower premiums. However, as explained in a recent report by Aon Hewitt, higher deductible plans can experience greater relative premium increases when driven by growing health care costs. (See the “Fixed cost-sharing e!ects (e.g., deductible leveraging)” section on page 7 of the Aon Hewitt report. The rest of the report is worth a read too.)

The underwriting cycle. Insurers carry reserves. Depending on the return they receive on them, they adjust premiums accordingly. This causes some quasi-periodic wiggles in premiums, which can be seen graphically here, here, and here.

Insurers are required by state regulators to invest conservatively (pdf). They’re heavily tilted toward bonds, which means their returns are sensitive to interest rates. In an analysis of the underwriting cycle from 1960-2004, Santrerre and Born found that premiums are negatively correlated with the Federal funds rate (pdf).

[W]e find that, for the period studied, health insurance premiums fluctuated because insurers attempted to keep up with expectations of future discounted claims costs as captured by prior claims costs and interest rates.

As the Federal funds rate goes down, premiums go up. Today, that rate is about as low as it can be.

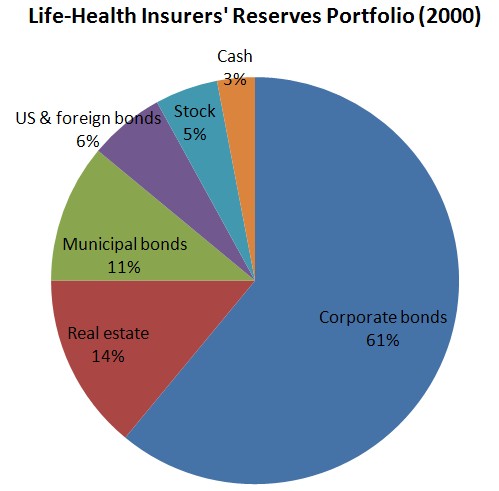

Harrington and Niehaus (page 94) document that in 2000, life-health insurers’ investments were dominated by corporate bonds and included only 5% stock and 14% real estate (chart below).

But that was 2000, ancient history in investing terms. Did insurers participate in the flight to safety over the past few years? Are they more heavily invested in low yielding US bonds today? It’s possible, but I don’t know. If they are, it’s not likely insurers are getting great returns. In fact, that’s probably true no matter how they’re invested, in part because they tend to invest short term. Who is making money on safe, short term investments these days?

Consequently, to make up for low returns on short term bonds, including Treasuries (either in absolute terms or relative to expectations), perhaps insurers are increasing premiums, as well as fees to self-insured plans for which they serve as administrators.

Is monetary policy and the bad economy increasing your premiums? It is quite plausible.