If you’re interested in the Affordable Care Act’s 2.3% medical device excise tax (pro, con, or neutral), you should read the Congressional Research Service’s economic analysis of it. You might also want to pay attention to The Center on Budget and Policy Priority’s take.

Though no stranger to the limelight, repeal of the tax has received growing attention in wake of the midterm election that will bring a Republican majority to the Senate. But the politics of the tax has far outpaced its economic import.

There are reasons to dislike the tax. It’s not a particularly efficient one since it is levied on a narrow base. And, it’s not a particularly socially important tax. After all, the intent of medical devices is to help, not harm, individuals. Therefore, discouraging the use of them with a tax isn’t something that we, in general, should welcome.

But we shouldn’t get too worked up. In the scheme of things, it’s not a large tax. CRS estimates the net effect on the industry is $29B over 10 years. It therefore won’t have a large effect on health care spending, estimated to be about $40T over that span. ($29B is less than 0.1% of $40T.) By the nature of the market and the fact that half of it is exempt from the tax, it won’t lead to substantial job losses, 0.2% of medical device industry jobs at most. And it won’t hurt U.S. competitiveness, since the tax is levied on imports as well as domestically produced devices.

Still, if the tax is repealed, we’d need to make up the $29B loss somehow. And it is true that additional spending on medical devices is likely with coverage expansion, which is a typical justification for taxing the industry.

But who really pays this tax? CRS makes a very good argument that it’s not the industry, but consumers, through higher medical bills and insurance premiums. Abstracted from any particular industry, Mike Piper and I made the same argument in our book.

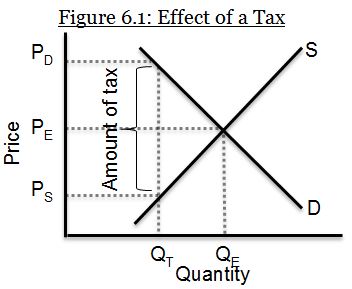

In the presence of a tax, we know that the revenue received by the sellers must be equal to the total price paid by consumers, minus the amount of the tax. So, to find the new post-tax equilibrium, we must find the quantity at which consumers’ willingness to pay (as shown by the demand curve) is higher than the minimum amount suppliers would be willing to accept (as shown by the supply curve) by an amount equal to the tax. […] In Figure 6.1, QT designates the quantity of the good that would be transacted in the presence of the tax.

As you can see from Figure 6.1, relative to the free-market (no tax) equilibrium, the net effect of a tax is to raise the purchase price (from PE to PD) and reduce the seller’s revenue (from PE to PS). The difference between PD and PS is the value of the tax. […]

What determines how much of a tax the buyer or seller pays (relative to the equilibrium) […] are the supply and demand elasticities. […] [I]n Figure 6.1, PD is about as far above PE as PS is below it. [So buyer and seller split the tax about equally.] But if the elasticities were different, this would not be the case.

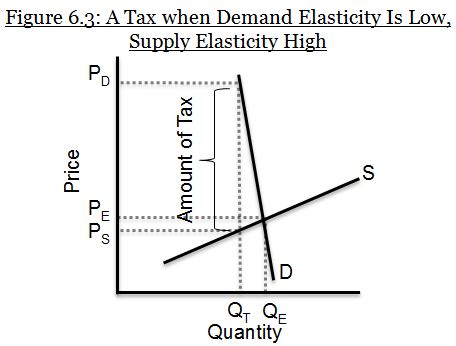

Figure 6.3 illustrates the case of a tax when the demand elasticity is low and the supply elasticity is high. In this case, the buyer pays the vast majority of the tax (PD-PE) and the seller pays very little (PE-PS). It’s the entity with the lower elasticity that pays more of a tax.

Figure 6.3 illustrates exactly the type of situation CRS believes to hold for medical devices. It’s very similar to their Figure 1. The supply of medical devices is highly elastic (a small change in price leads to a large change in quantity) because the market is highly competitive. (For medical device products for which this is not the case, CRS offers a different argument that leads to the same conclusion.) The demand for medical devices is highly inelastic (even when price changes considerably, pretty much the same quantity is demanded). There are a number of reasons for this including that most consumers are insured for medical devices (making them less price sensitive at time of use), consumers trust doctors when they suggest a medical device is needed (either explicitly or implicitly through bundling with a procedure or therapy), and it’s hard to hold back on medical care viewed as necessary, even for a higher price, while one doesn’t buy a ton more at lower prices (we only have, at most, two knees and hips, after all).

This leaves us with a puzzle. It’s easy to see how something like the medical device tax can become a political football. We’re accustomed to politics existing in an evidence-free space, unfortunately. But given that consumers (mostly through insurance) will pay the lion’s share of the cost of the medical device tax and given that there are not likely to be other substantial effects on the industry, why is the industry so opposed to it?

UPDATE: One reason the industry might oppose it is that the market analysis described in this post doesn’t apply to administered pricing systems, like Medicare, Medicaid, and the VA. For those, costs can’t be passed on to consumers because the government pays fixed prices on their behalf. The way device manufacturers get more money is through a political process, which justifies some vocal opposition and lobbying. H/t to Aaron for raising this point. The CRS report did not do so, unless I missed it.