In 2000, the AAP published a guideline recommending to decrease the risk of a child developing an allergic disease. They recommended that “mothers should eliminate peanuts and tree nuts (eg, almonds, walnuts, etc) and consider eliminating eggs, cow’s milk, fish, and perhaps other foods from their diets while nursing. Solid foods should not be introduced into the diet of high-risk infants until 6 months of age, with dairy products delayed until 1 year, eggs until 2 years, and peanuts, nuts, and fish until 3 years of age.”

In 2006, along with colleagues like Beth Tarini, we published a systematic review of the early introduction of solid foods and the later development of allergic disease. We found, somewhat to many people’s surprise, that while there was some evidence linking early solid feeding to eczema, there was no strong evidence supporting a link between early solid food exposure and the development of asthma, allergic rhinitis, allergies to animals, or persistent food allergies.

In other words, there was no good evidence to keep infants away from foods in the belief that we could spare them food allergies later. Other studies showed a similar lack of evidence for the other parts of the recommendation. In 2008, the AAP altered its recommendations to say there wasn’t good evidence to support food avoidance to prevent allergies.

A study in the NEJM today goes a step further. It says that keeping peanuts away from infants may be making things worse:

Background: The prevalence of peanut allergy among children in Western countries has doubled in the past 10 years, and peanut allergy is becoming apparent in Africa and Asia. We evaluated strategies of peanut consumption and avoidance to determine which strategy is most effective in preventing the development of peanut allergy in infants at high risk for allergy.

Methods: We randomly assigned 640 infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both to consume or avoid peanuts until 60 months of age. Participants who were at least 5 months but younger than 11 months of age at randomization, were assigned to separate study cohorts on the basis of preexisting sensitivity to peanut extract, which was determined with the use of a skin-prick test – one consisting of participants with no measurable wheal after testing and the other consisting of those with a wheal measuring 1 to 4 mm in diameter. The primary outcome, which was assessed independently in each cohort, was the proportion of participants with peanut allergy at 60 months of age.

They took 640 high risk infants and randomized them to get peanuts or not for the first 5 years of life. They separated kids in both intervention groups by any pre-existing sensitivity to peanuts. Then they checked them at 5 years of age to see if they had a peanut allergy.

I have friends who will already have lost their minds hearing about this. I mean, letting kids get exposed to peanuts? Especially kids with a sensitivity to peanuts already? Insane, right? Until you see results like this:

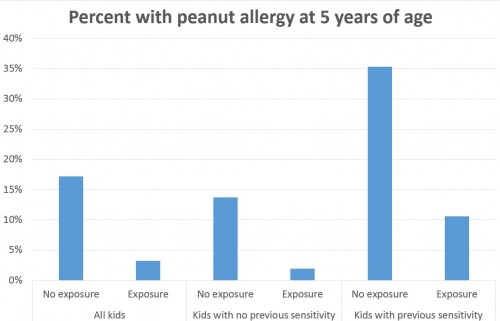

Looking at all kids, about 3.2% of those exposed to peanuts developed a peanut allergy, as opposed to 17.2% of those not exposed to peanuts. If you only look at the kids without prior peanut sensitivity, about 1.9% of those exposed to peanuts developed a peanut allergy, as opposed to 13.7% of those not exposed.

But in the cohort of kids with a known peanut sensitivity already, exposure to peanuts until age 5 years led to a prevalence of peanut allergies of 10.6%, versus 35.3% in those not exposed.

In other words, exposing kids to peanuts, even those with a sensitivity, led to fewer allergies. Conversely, not exposing them led to more allergies. I mean, kids with a previous sensitivity to peanuts who were exposed to them had a lower prevalence of peanut allergies at 5 years of age than kids who didn’t have a previous sensitivity to peanuts, but were never exposed to them. The accompanying editorial pulls no punches:

[W]e believe that because the results of this trial are so compelling, and the problem of the increasing prevalence of peanut allergy so alarming, new guidelines should be forthcoming very soon. In the meantime, we suggest that any infant between 4 months and 8 months of age believed to be at risk for peanut allergy should undergo skin-prick testing for peanut. If the test results are negative, the child should be started on a diet that includes 2 g of peanut protein three times a week for at least 3 years, and if the results are positive but show mild insensitivity (i.e., the wheal measured 2 mm of less), the child should undergo a food challenge in this peanut is administered and the child’e response observed by a physician who has experience performing a food challenge.

We’re seeing an alarming increase in peanut allergies worldwide. Our response appears to be making things worse. Time to change our behavior here.