I hate to say it, but the more I experience the health care system the more I recognize how much health care is not worth its price. I’m not saying all medical care is useless. Far from it. Some things are well understood, and some cures are effective and life-saving. I’m just saying the limitations of medical science and medical practice are larger than most realize or admit, including my younger self.

This sentiment was expressed clearly in Christie Aschwanden’s recent piece in Miller-McCune (h/t Kaiser Health News).

A surprising number of medical practices have never been rigorously tested to find out if they really work. Even where evidence points to the most effective treatment for a particular condition, the information is not always put into practice. “The First National Report Card on Quality of Health Care in America,” published by the Rand Corporation in 2006, found that, overall, Americans received only about half of the care recommended by national guidelines.

Certainly we can learn more with research of the right type. And we should do more about aligning financial incentives with good practice and the following of effective guidelines. Naturally, there is the potential (but not a certainty) that more funding for comparative effectiveness research can help. Aschwanden:

A $1.1 billion provision in the federal stimulus package [will provide] funds for comparative effectiveness research to find the most effective treatments for common conditions. But these efforts are bound to face resistance when they challenge existing beliefs. … [N]ew evidence often meets with dismay or even outrage when it shifts recommendations away from popular practices or debunks widely held beliefs.

Aschwanden’s piece goes on to describe how to present evidence to convince practitioners and the public to change firmly held but incorrect beliefs. There’s a mistaken idea that the truth will simply be accepted, when in fact people are generally unable to shed their false mental models. “How do you convince doctors and patients to dump established, well-loved interventions when evidence shows they don’t actually improve health?” she asks.

Aschwanden’s solution is to emphasize the narrative, even the argument by analogy, not the cold, hard facts. This gets to the issue of what most people take as evidence. People like stories, not numbers. It isn’t the facts they need updated so much as their mental model. Shifting belief is less about marshaling the latest research and more about appealing to intuition.

Proponents of comparative effectiveness research look for answers in large-scale trials, but these studies hinge on statistics about large groups of people. Such number crunching rarely has the power of personal anecdote.

That’s all fine, as far as it goes, but it misses a key point. We do need the studies and evidence first. Only then can we figure out how to present empirical findings in a convincing way. But what constitutes scientific evidence? Must comparative effectiveness research necessarily be conducted by clinical trial? A randomized trial can produce the most convincing evidence, but it isn’t always practical or possible (recall my debate with Robin Hanson on this point).

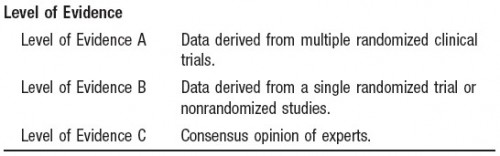

Observational studies using sound methods that exploit non-experimental randomness can provide high quality evidence. This fact and the associated technique (instrumental variables) are understood by many economists, some physicians, and too few epidemiologists (I eagerly await the day when I’m convinced otherwise). Results from such studies can influence thinking and practice. The American Heart Association and American Stroke Association consider a collection of nonradnomized studies to be an equivalently convincing source of evidence as a single randomized trial, though less convincing than data from multiple randomized trials, which is a sensible position (see figure below from their guidelines).

Unfortunately, far too much thinking in medicine and in the rest of our lives is based on the lowest form of evidence, if any. The consensus opinion of experts may be better than nothing but not necessarily. The history of medicine (and most human endeavors) has shown time and again that opinion, even consensus opinion, is often wrong, sometimes tragically so. Moreover, far too often consensus or even one’s own opinion is allowed to override more objective forms of evidence. That’s the psychological problem Aschwanden addressed and may be the most important fact of all.