This post is coauthored by Austin Frakt and Aaron Carroll.

We have already written many posts about Singapore’s health system (there’s a a tag for that), which is built around medical savings accounts (it’s Medisave program), though encompasses so much more. Unsurprisingly, we’re far from the first to comment on the system. But, contrary to what some have suggested, we’re not just interested in scoring political points. We want to know what data and evidence have to say about Singapore. This post summarizes a few points from some of the relevant literature from peer-reviewed journals.

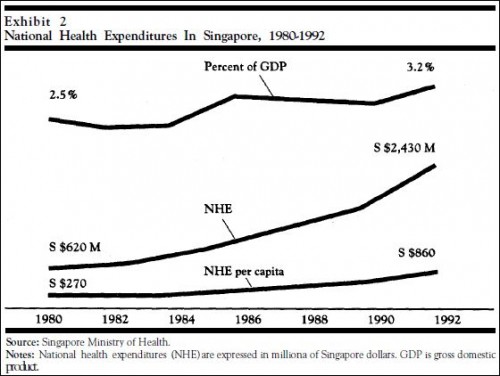

Scholarly literature on Singapore’s health system goes back at least as far as the 1995 Health Affairs paper by William Hsiao. (His paper is ungated. Ungated versions of those linked below may also exist. Use Google Scholar.) He described the country’s health spending trajectory just before and after Medisave was introduced. Medisave, you might remember, is the major source of cost-sharing for the people of Singapore:

The per capita cost of health care in Singapore, in fact, rose faster after the introduction of the Medisave program in 1984 (Exhibit 2 [below]). Health expenditures per capita rose at an average rate of 13 percent per year-2 percent faster than the average before the introduction of Medisave. Part of this accelerated rate of increase was attributable to the upgrading of public hospital facilities but mostly caused by other factors. […]

In spite of the high average rate of growth in GDP of 10 percent, Singapore’s health expenditures grew faster, rising from 2.5 percent to 3.2 percent of GDP between 1980 and 1993.

In other words, health care spending increased after the introduction of increased cost-sharing, which is not what most proponents of such changes would expect. These points are repeated in Michael Barr’s “critical inquiry” into Singapore’s medical savings account, published in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law (JHPPL) in 2001. But this was not a randomized controlled trial, and causality is, of course, not proven.

In an accompanying commentary, Mark Pauly responded with two valid points, among others. First, it’s been well established that the more something costs an individual, the less of it they buy. It’s even been established for health care. Cost sharing definitely matters. Second, casual, pre-post examination of time series is uninformative about the effects of an intervention. How would Singapore’s health spending have changed in the absence of the Medisave intervention? We don’t know.

Compounding the difficulty in judging Medisave from a time series is that it was not the only intervention. It seems to be uncontroversial in Singapore that substantial government involvement (some may call it “intrusion”) in the health care market is necessary for good performance. Hsiao quoted a 1993 Singapore Ministerial Committee on Health Policy white paper, the first few pages of which can be viewed here:

Market forces alone will not suffice to hold down medical costs to the minimum. The health care system is an example of market failure. The government has to intervene directly to structure and regulate the health system.

Barr quoted a different passage of the same document justifies rationing, including by government intervention:

We cannot avoid rationing medical care, implicitly or explicitly. Funding for health care will always be finite. There will always be competing demands for resources, whether the resources come from the State or the individual citizens. Using the latest in medical technology is expensive. Trade-offs among different areas of medical treatments, equipment, training and research are unavoidable.

Intervene, the government did. In Health Affairs, Thomas Massaro and Yu-Ning Wong described some of the interventions, including control of physician and hospital supply, generous subsidization of hospital care, and hospital revenue caps. They wrote,

Financing mechanisms alone do not define a health care system. Singapore has a clearly delineated policy that works in its setting. The state actively participates in every aspect of the delivery system, from physician supply to price setting and the establishment of service criteria. This willingness to intervene aggressively in the market (at levels probably unacceptable to most Americans) may be as important as the individual savings mechanism to its success.

In a JHPPL commentary that accompanied Barr’s paper, Hsiao described other means of cost control.

MediShield [Singapore’s opt-out, catastrophic health plan] adopted the risk selection practices of private insurance schemes by excluding as enrollees persons aged seventy and older and by not covering some expensive services, such as treatments for congenital abnormalities, mental illness, and HIV/AIDS. [Some of these policies may have changed since the paper’s publication in 2001.]

Again, however, point granted to Pauly that some restrictions imposed by Singapore’s government are not altogether different from those imposed by commercial plans in the U.S., for better or worse. We take this to mean that there really aren’t all that many ways to control costs in all areas. Ultimately, you have to say “no” in some fashion.

In another JHPPL commentary, Chris Ham makes what we think is the most important point:

The broader lesson from Singapore is that health care reform continues to swing back and forth between a belief in market forces and the use of government regulation. In reality, health policy is replete with examples of market failures and government failures as policy makers experiment with different instruments. The variety of health care systems developed around the world indicates that the choice is neither pure markets nor government control but the balance to be struck between the two. And to return to our starting point, where the balance is struck will be shaped by social values and the political choices that follow from them.

There’s one more challenge in assessing Singapore’s health system, raised by Barr.

The government is highly secretive about the detailed operation of its system and has not made either the data source or method of its calculations available to anyone outside those in the Civil Service and the government who need to know—not to the public; not to academic researchers.

This probably explains why, though there is a literature on the Singapore health system, it’s a modestly sized one. It should also cause anyone serious to hesitate before advocating that Singapore’s system, and its results, can be generalized without some concerns.

By the way, JHPPL also published a letter to the editor by Meng-Kin Lim (we gather this is his homepage) and responses from Michael Barr and William Hsiao. Finally, here’s a paper that compares Shanghai’s experience with medical savings accounts to Singapore’s.

The bottom line is that Singapore isn’t simply “cost-sharing”, “free market”, “competition”, and a “lack of government involvement”. If you endorse Singapore’s health care system, you’re buying into many things, and some truths, that libertarians and conservatives claim to dislike. We acknowledge that more cost sharing can reduce spending. But if that’s the only thing you endorse, then you’re not talking about Singapore.