Spotlight dramatizes the Boston Globe’s investigation of sexual abuse by Roman Catholic priests. The movie’s victims, perpetrators, enablers, and most of the journalists are Catholics. But it’s too easy to see this as a Catholic problem. The story is about men, not Catholics; about powerful institutions and how they can protect themselves from scrutiny; and about why we need strong, independent journalism.

In 2001 and 2002, Globe journalists documented that there were (at least) 87 sexually abusive priests in the Boston archdiocese. Moreover, these priests were known to their religious authorities. When the priests’ abusive behaviour was discovered, the Church hierarchy colluded with police and the courts to suppress prosecution of or publicity about the crimes. Victims were powerless and the abuse just went on.

But are Catholic priests more likely to commit abuse than other men? For obvious reasons, it is hard to find reliable data. Criminologists at John Jay College estimated that 4% of US Catholic priests have had allegations of sexual abuse. How often do men in other settings abuse children unrelated to them? A survey in Finland found that 4% of girls living with a stepfather reported being sexually abused by that man. A report by the US Department of Education found that 7% of students experience unwanted sexual contact by an educator (male or female) sometime during primary or secondary schooling. Neither of these rates is directly comparable to the John Jay estimate, but they suggest that a child’s risk of experiencing sexual abuse is small but ubiquitous. Abuse occurs in schools, summer camps, sports teams, and — let’s face this — health care institutions. Because perpetrators are predominantly (but not exclusively) male, the relevant question might not be “what’s wrong with priests?” but rather “what’s wrong with men?”

The policy question, then, is how institutions should manage this risk. It seems self-evident that they should obey laws that mandate reporting of criminal abuse. For unethical conduct falling short of crime, institutions should follow internal disciplinary procedures or report abusers to their professional organizations.

But I am old enough to have seen universities and hospitals handle more than one instance of sexual misconduct. My experience is that institutions fear scandal and seek to minimize disclosure. And that unless there are women in leadership, there will (still!) be ‘old boy’ networks that ‘understand’ how a perpetrator ‘was under a lot of stress’, and want to rationalize a failure to report.*

We can’t realistically expect institutions to effectively police themselves unless they face severe consequences for not doing so. The courts are critical here, but sometimes they fail us. The message of Spotlight is that independent investigative journalism is indispensable for the public accountability of our institutions.

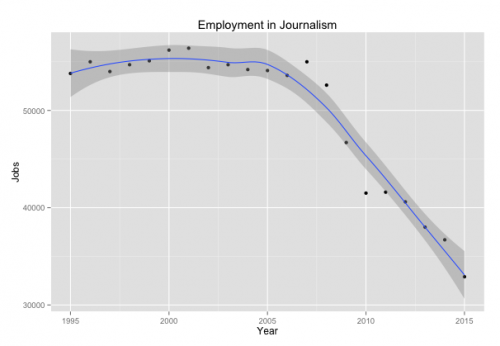

But how long will we have journalists who can do this? The graph below plots data from the Niemanlab showing that jobs in journalism have fallen 40% since the beginning of the Great Recession, with no end currently in sight.

The Spotlight team still exists (and did a great job in reporting on how Boston’s elite healthcare institutions “are paid much more for care that is often no better than average”). But it’s likely that a lot of one-time investigative journalists have lost those jobs.**

See the movie. Spotlight is understated, well-written, well-acted, and authentic. I grew up in several towns in Greater Boston. Michael Keaton (playing Robby Robinson, the leader of the Spotlight team) perfectly captures the Irish Catholic dad of so many of my friends: tough, taciturn guys who were a hell of a lot smarter than they wanted anyone to know.

*Which is not to say that abusers do not need and deserve treatment. Spotlight has a wonderful moment in which a journalist (Rachel McAdams playing Sacha Pfeiffer) unexpectedly meets an abusive priest. He’s a sad, confused, and victimized man who clearly needed care, close supervision, and perhaps employment in a different environment. But professions aren’t professions unless they have ethical discipline, with teeth.

**A point of hope is that some of the work by the Spotlight team would be easier today. The Globe identified most of the abusive priests by spending weeks correlating records from registries of where priests served in the archdiocese. They found priests who had been transferred in ways that suggested that they might have been abusers. Today, I could do this in a day with a Python interpreter, assuming I had access to the databases and the brains to ask the right question.