I’m afraid this is a wandering post, featuring the calculus of variations, a Facebook invite from an old girlfriend, and the ethics of end of life care. I hope it’s worth it.

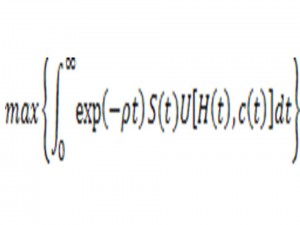

Yesterday I went integral with a column about Kevin Murphy and Robert Topel’s great paper, “the value of health and longevity.” I noted that Murphy and Topel solve a forbidding-looking dynamic optimization problem. I didn’t have a chance to discuss some things missing there.

I first encountered such problems years ago, when I was a high school senior. My high school had few AP courses. So my friend Peter Magyar and I would take a bus across the Hudson River to take math courses at Columbia University. I remain grateful to my professors there, including a wonderful man named Lipman Bers, a refugee from Hitler who made great contributions to mathematics and physics.

During the 1700s, mathematicians Euler and Lagrange originated a beautiful branch of mathematics known as the calculus of variations to solve such problems. Indeed my lecture notes included Euler and Lagrange’s solution. By coincidence, I was piddling with Murphy and Topel’s equations when I received a Facebook “friend” request and a sweet email from the girl I dated as a high school senior when I first learned this stuff. We hadn’t crossed paths for maybe two decades. No harm done. Life moves on.

I accepted the friend request, and headed off to a stupefying meeting completing paperwork for our school’s Council on Social Work Education accreditation. My task was to write dozens of bullet points explaining how my introductory microeconomics course “articulates conceptual frameworks,” “delineates structural inequalities facing vulnerable populations,” yada yada. Yes, the entire exercise resembled a National Review parody of liberal group-think. (I write this as someone who really does try to delineate structural inequalities facing vulnerable populations. I never, however, knowingly articulate any conceptual framework.)

This task of typing approved action verbs into our reaccreditation materials left plenty of CPU time to ponder cringe-inducing memories of actual and attempted romances of my younger years. The power of these memories commands me to treat my teenage daughters’ own romantic triumphs and disappointments with the respect and the seriousness these experiences deserve. The sweetness and the painful experiences stay with you, decades later. Typing away, I wondered how my life was changed by my relationship with this girl, and how this now-middle-aged woman regards my own teenage self in her own biography all these years later.

I’m not going to go all Lifetime Channel on you, Rather, I’m going to go back to economic theory, pondering whether my sweet email exchange suggests Murphy and Topel’s beautiful equations were missing something. These authors envision that we add up a stream of utilities generated by current health status and current consumption. That’s a powerful and useful framework. Unfortunately, some important things in life, in medical care, in public policy don’t readily fit that—dare I say—conceptual framework.

Tom Schelling, in his brilliant essay “The mind as a consuming organ,” writes: “The human mind is something of an embarrassment to certain disciplines, notably economics, decision theory, and others that have found the model of the rational consumer to be powerfully productive.”

Schelling reminds those of us steeped in the economic tradition of something very basic. Our most important experiences are “consumed,” so to speak, within our minds. We care about things that happened a long time ago that will never–outside the mysterious space of our own heads–materially affect our lives again. We continue relationships with people we may never cross paths with again. We have a life story. We have precious and painful memories. We care about the people who appear in it, even if they are not currently on the stage. It goes the other way, too. My life goes on in my roles in other people’s life stories. Sometimes I am a key player. Mostly I play a cameo role.

Emails from old girlfriends play well on TV; they’re rarely the most important thing here. Some of us spend thousands of dollars on psychotherapy to unpack what really happened in some childhood incident involving our parents. A mother or father may be dead and buried. The relationship continues, and it’s important. Did my dad enjoy spending time with me? Did my mother think I was smart or that I was pretty?

Some of the same issues arise when we consider knife-edge questions of public policy. Consider one especially delicate arena: End of life care.

Why (say) do we spend $100,000 on medical care for a patient with metastatic cancer during the last few weeks of her life? Why is it hard to show greater restraint, even when much of this care appears futile? Ezra Klein today cites an essay in which a retired nurse says: “I am so glad I don’t have to hurt old people anymore.” Why is it so hard to say “stop,” when aggressive care for a clearly-dying patient appears to fail any cost-utility test and may even hurt people?

If it were simply stupid or greedy to over-treat like this, this would be a much easier problem than it actually is. To put things another way: It’s easy to overlook powerful reasons and motivations to provide what would otherwise appear to be futile and costly care. I wouldn’t deny that institutional routine, financial incentives, sloppy standard operating procedures of hospitals and medical specialties are important. We don’t really need bioethicists to address overuse of costly support therapies such as Epogen or the conflicts of interest in advanced cancer care.

But something else matters, too: What’s going on in the heads of the children, siblings, partners, and friends whose loved-one lays dying in the hospital ICU. Much end-of-life care, for good or ill, is not really helping the patient. It’s helping the people that patient leaves behind.

I am absolutely healthy. But someday I will die, hopefully someday very far in the future. My survivors may then wonder: Did I show my father (my husband, my friend) that I loved him? Did I give up too soon? Did I get the chance to thank him for that act of kindness, to forgive him for that mean thing he once did? Did he trust me to decide for him matters he could no longer decide for himself? Was that trust misplaced? Did our family come together to approach this life-altering moment in ways that brought us together rather than tore us apart?

When you combine this with the absolutely human wish to keep hope alive as we witness the annihilation of a dying loved one, it’s hardly surprising that we aren’t ready to say “stop.”

I fear that my survivors, presumably my wife and children, might suffer in answering these questions. I play an important role in their life stories. I will still be important after I am gone. Whatever will happen over my final two weeks, I will experience it for only two weeks. My survivors will live with whatever happens for decades, maybe for the rest of their lives. If spending $100,000 on my final two weeks provides them greater consolation, maybe that’s okay.

Of course, once we frame things this way, we might ask if that same $100,000 could be spent with greater humanity and greater restraint to produce some of the same beneficial effects. There are better ways to say: “I love you, and I will miss you” than to beat the heck out of someone we love through desperation treatments that no longer work.

We, the future patients, can help, too. We can reassure the people we will leave behind. We know that hard decisions will be made in life’s endgame we can’t completely specify in advance. We can tell our families: I know that you will do your best. I know that you love me. It will be sad but okay. Whatever my physical endgame, my life will go on in you.